NORMALLY, celebrations mark the culmination of a successful event.

The recent Trump-Kim Summit in Singapore reversed the process and served as a media spectacle that gave very little insight into what North Korea was offering after discussions between US President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un.

But it did showcase Singapore’s willingness to perform the role of accommodating host par excellence; more than just serving coffee and tea and taking wefies with Kim, but footing a sizable $20 million tab and hopefully putting that money back into the economy.

But, balance that against accounts of life in North Korea under Kim’s ancestors, and draw your own conclusions.

Hyeonseo Lee’s story about the country she grew up in, sheds light on the realities as she remembers them. Born in North Korea, she defected as a teenager and now resides in South Korea.

A human rights activist, she holds little optimism for any positive outcomes from the Trump-Kim Summit.

As a schoolgirl in North Korea, Lee was forced to watch executions, denounce her friends for fabricated transgressions and dig tunnels in case of a nuclear attack.

But Lee and her classmates grew up convinced they lived in the “greatest nation on earth” run by a benevolent god-like leader whom they loved in the way many children love Santa Claus.

Related Article

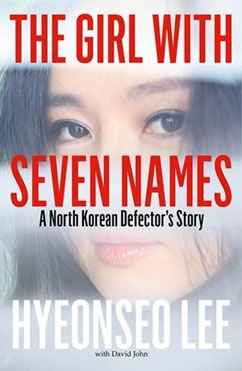

It wasn’t until she left North Korea at the age of 17 that she began to discover the full horror of the government that had fed her propaganda since birth. In her 2015 memoir, The Girl With Seven Names, Lee gives a rare insight into the bizarre and brutal reality of daily life in the world’s most secretive state.

Living In Another Universe

“Leaving North Korea is not like leaving any other country. It is more like leaving another universe,” she writes in her book. “Nearly 70 years after its creation it remains as closed and as cruel as ever.”

Lee, now a human rights campaigner living in South Korea, grew up in Hyesan next to the Chinese border. She had a close family with an array of colourful relatives including “Uncle Opium” who smuggled North Korean heroin into China.

All family life took place beneath the obligatory portraits of North Korea’s revered founder Kim Il-sung and his son Kim Jong-il which hung in every home. Failure to clean and look after them was a punishable offence.

At supper, Lee had to thank “Respected Father Leader Kim Il-sung” for her food before she could pick up her chopsticks.

Her family was well regarded and her father’s job in the military meant they were not short of food. But brutality and fear were everywhere.

The faintest hint of political disloyalty was enough to make an entire family — grandparents, parents, and children — disappear. “Their house would be roped off, they’d be taken away in a truck at night, and not seen again,” she says.

As Lee entered her teens her world was turned upside down when her father was arrested by the secret police. He was later released into a hospital. He had been badly beaten and died soon afterward. The circumstances remain unclear.

Lee says one of the tragedies of North Korea is that everyone wears a mask, which they let slip at their peril.

“Kindness towards strangers is rare in North Korea. There is a risk to helping others,” she writes. “The state made accusers and informers of us all.”

Public executions were used as a way to keep everyone in line.

Lee witnessed her first execution at seven. After Kim Il-sung’s death in 1994, she recalls a spate of executions of people who had not mourned sufficiently.

You Might Also Like To Read:

Property Trends — Boon Or Bane?

Will Azalea Bloom With Astrea IV?

More Death To Come

In the mid-1990s North Korea suffered a famine, which killed an estimated one million people. Lee’s first inkling of the crisis came when her mother showed her a letter from a colleague’s sister living in a neighbouring province.

“By the time you read this the five of us will no longer exist in this world,” it read, explaining that the family were lying on the floor waiting to die after not eating for weeks.

Lee, who still believed she lived in the world’s most prosperous country, was stunned. A few days later she came across a skeletal young mother lying in the street with a baby in her arms. She was close to death, but no one stopped. Beggars and vagrant children began to appear in the town and corpses turned up in the river.

“The smell of decomposing bodies was everywhere,” Lee said.

In her book, she describes taking a train through a “landscape of hell” to visit a relative. She saw people roaming the countryside “like living dead”. In the city of Hamhung she recalled people “hallucinating from hunger” and “falling dead in the street”.

The government blamed the famine on US sanctions, but she later learnt it had more to do with the collapse of the Soviet Union, which had been subsidising North Korea with food and fuel.

Power cuts became increasingly frequent. At night Lee would stare across the river to the twinkling lights of China and wonder at the contrast with the darkness that shrouded her own city. Her fascination was fuelled by the Chinese satellite TV she watched illegally after blacking out the windows.

One winter night in 1997 she slipped out of the house and crossed the narrow stretch of frozen river by her home with the help of a friendly guard. Lee’s defection started off as a prank — she simply wanted to see what China was like.

When her mother finally tracked down her daughter to a distant relative’s home in China, her first words on the phone were “Don’t come back.”

Many New Identities

But China was not safe either. Lee lived in fear of being unmasked and deported back to North Korea, where she would have been imprisoned or even killed. To survive she changed her name numerous times — hence the book’s title.

She had many close shaves: she narrowly escaped an arranged marriage, almost became enslaved in a brothel, was kidnapped by a gang of criminals and caught and interrogated by police. Lee managed to persuade the officers she was Chinese, thanks to her mastery of the language and her quick wits.

After years on the run, she reached South Korea where North Koreans are given asylum. But she missed her family desperately. In a daring mission, she returned to the North Korean border to rescue her mother and brother and guide them 3,200km through China into Laos and from there to South Korea — a journey beset by disaster from start to finish.

Since settling in South Korea, Lee has become an advocate for North Korean human rights and refugee issues, addressing the United Nations and the US Committee on Human Rights. Her fans include US chat show host Oprah Winfrey.

The name Lee uses today is not the one she was given at birth, nor one of those forced on her by circumstance.

“It is the one I gave myself, once I’d reached freedom,” she writes. “Hyeon means sunshine. Seo means good fortune. I chose it so that I would live my life in light and warmth, and not return to the shadow.”