IN THIS period of restriction, and potential job losses, many people might be thinking about what they are going to do next.

Starting a mask making business might be top of mind for many since there may not be a job out there to be had. But that means getting the word out about what you have to offer, and possibly setting up a website to showcase your products.

To differentiate your mask, you may print “09876abc” on the masks to identify your handiwork.

After pictures of your masks are shared on social media and go viral, you start getting many orders. As sales of “09876abc” masks pick up, you decide to set up a webstore at “09876abcmask.sg”.

But, when you try to register the domain name, you are shocked to find out that somebody has beaten you to this name, and other permutations of it (such as 09876abcmask.com, mask09876abc.com.sg).

To rub salt into the wound, you get a message from the owner of the domain offering to sell you those domain names for $1,000 each, while bragging about how smart he was to see the business potential in your masks when it went viral. He suggests he might sell it to a competitor if you don’t buy the domain names from him.

So, what can you do about this?

ALSO READ: The New Travel Protocols

Domain Name Registration

Like physical addresses, domain names are accessible forms of Internet addresses that link Internet users to websites. Domain name registration is typically quick and inexpensive, requiring just a nominal fee. The problem, however, is that registration is on a first-come, first-served basis.

Now, not only do businesses have to be careful about infringing the trademarks of other businesses, they may also face challenges in securing domain names for themselves. In recent years, it has become an increasingly common phenomenon for domain names incorporating the names of established businesses to be purchased by third parties, and which are then sold at much higher prices exceeding the cost of registration to businesses that own the trademarks or to other interested parties, including competitors.

Technological developments and the introduction of new generic top level domains (eg .asia, .shop, .online) make businesses more vulnerable to such practices. This is further compounded by lack of regulations and difficulties in establishing international legal standards.

ALSO READ: Are We Closer To A Covid-19 Treatment?

Is Cybersquatting Legal?

Is it legal to register domain names you do not intend to use?

Before considering the legality of such practice, we must first understand the concept of cybersquatting.

There is no statutory definition of cybersquatting in Singapore. According to the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO), “cybersquatting” is most frequently used to describe the practice of “deliberate, bad faith abusive registration of a domain name in violation of rights in trademarks”. For instance, when someone with no connection to a well-known or established business name (e.g. Coca-Cola) registers domain names which have not been registered by the real owner of that business, such as cocacola.sg, cocacola.my, and cocacola.asia.

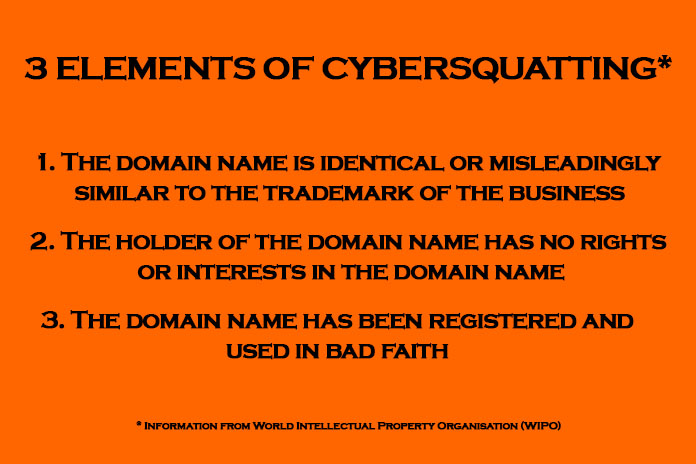

The Singapore High Court considered the issue of cybersquatting for the first time in a recent case involving Grab. In determining whether the registration of a domain name was considered abusive, the High Court considered the following conditions established by WIPO.

Bad faith would be found where:

• The domain name holder offered to sell, rent, or transfer the domain name to the actual owner of the trademark or to a competitor for “valuable consideration”;

• The domain name holder attempted to attract, for financial gain, Internet users to his own website or other websites, by creating confusion with the actual trademark (e.g. linking cocosg to your own webstore selling unlicensed coca cola merchandise);

• The domain name was registered to prevent the actual trademark owner from using his mark in a domain name, and the domain name holder was engaged in a pattern of such behaviour; or

• The domain name was registered to disrupt the business of a competitor.

The High Court took the view that these WIPO criteria were the same as the framework under the Singapore Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (SDRP). Therefore, to establish cybersquatting in Singapore, you must show that the domain name holder’s actions meet the above WIPO conditions.

ALSO READ: Law Firms Prepare For The Post-Pandemic Era

Cybersquatting Or Domain Speculation/Investment?

In Singapore, cybersquatting is not prohibited by statute.

However, after the comments of the High Court in the Grab case, it is likely that a contract which facilitates cybersquatting would not be enforceable in Singapore (e.g. a contract to sell grab.com.sg to Grab).

The High Court took the view that the abusive usage of domain names must be curbed given the widespread and pervasive use of the Internet today. Nonetheless, the law remains unsettled as the High Court’s comments were not binding.

You may then wonder if there is a difference between cybersquatting and domain name speculation or investment. Domain name speculation is generally understood as the practice of identifying and registering domain names as an investment with the intention of selling them later for a profit.

The High Court did not elaborate on the distinction between the two. WIPO’s position seems to be that such a practice would be permitted if the domain name was not registered in bad faith.

In another dispute involving the domain name dialoga.com, WIPO had to consider whether the domain name holder was a cybersquatter as the complainant company had trademarks similar to “dialoga.com”. Despite that the complainant had registered trademarks even before the registration of dialoga.com, WIPO decided that there was no cybersquatting.

The decision hinged on the issue of bad faith. Although WIPO found that the domain holder had registered dialoga.com with the intention to offer it for sale, WIPO decided that this was in the nature of the domain holder’s business and was not done in bad faith.

Crucially, the word “dialoga” was a common dictionary word in no less than three languages (including Spanish, Italian and Portuguese) and was used by many different companies for different purposes. There was also no evidence to show that the complainant was specifically targeted by the domain holder.

WIPO further noted that the timing of registration of the trademark and the disputed domain name alone are not sufficient to establish bad faith. Nor would the mere fact that the domain holder was aware of the complainant’s business or its trademarks prior to registering the domain name be sufficient. Something more would be necessary to demonstrate bad faith as opposed to merely benefitting from the presence and attractiveness of a generic word in the domain name.

The dialoga.com case also illustrates that “reverse domain name hijacking” should not be done. This is when you make a complaint against a domain name holder in bad faith. For example, when you made the complaint, you knew that you would not be able to prove that the domain name holder had registered the domain name in bad faith.

While WIPO thinks that domain name speculation and investment is not cybersquatting, in Singapore, the position is not entirely clear.

Complainants should therefore exercise extra caution and consider whether there is a good case of establishing cybersquatting before bringing any action against a domain name holder.

Protecting Your Interests

Given the lack of clarity and certainty in this area, it is all the more important that you carefully consider your business branding strategy and company name at incorporation. As illustrated in the dialoga.com case, the mere registration of trademarks alone may not necessarily provide sufficient protection.

Businesses should, where possible, take preventive measures as soon as possible to register their domain names for a nominal sum upon incorporation to avoid being embroiled in prolonged and costly disputes later.

It should be noted that the Intellectual Property Office of Singapore (IPOS) has collaborated with Singapore Network Information Centre (SGNIC) to provide free registration of .sg or .com.sg domain names with each successful registration of a trademark.

Businesses that have successfully registered their trademarks in Singapore should therefore take advantage of this scheme to register their domain names.

In the event a domain name has already been registered, you might file an administrative action against the holder to recover the domain name and have it transferred to you if cybersquatting can be established. This is a more cost-efficient out-of-court alternative.

The Singapore Mediation Centre will handle the administrative action in accordance with the Singapore Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (SDRP). A panel will be appointed to resolve the dispute, by way of mediation if both parties agree, otherwise the panel will resolve the dispute itself. You would have to establish the three elements of cybersquatting (see the WIPO conditions above) against the domain name holder. If you are successful, the SGNIC will transfer the domain name to you.

Certainly, you may sue the domain name holder in court if you have exclusive rights in the trademarks. However, court litigation is generally lengthy and expensive, and involves a high level of publicity which might not be good for your business.

Another alternative might be to negotiate with the holder of the domain name yourself.

Ultimately, the choice is a commercial one for you to make. This involves, among other factors, balancing the needs of your business, the importance of the domain name to your business, and the costs involved.

As it stands, the current law in this area is not entirely clear in some respects. Businesses should continue to observe developments in this area.

Coming back to the case of 09876abcmask.sg, there is no definite answer about what you can do.

It may be possible for you to take action against the person holding those domain names, and argue that he had acted in bad faith in registering those domain names as he had watched the development of your business and had intended to sell the domain names to you for a tidy profit.

However, if the price he is offering is not too high, it may be, unfortunately, simply more convenient and cost-effective to buy them from him.

Of course, it would be most ideal if you had registered the domain name as soon you knew you might expand online, though it is not always easy to predict the future online presence of your business.

David Teo Shih Yee is the Managing Director of Longbow Law Corporation. This article was prepared with the assistance of Ng Wei Lin and Kit Chan Kit Ho.

If you have a point of view on COVID-19, or think someone you know could present a thought-provoking perspective on the subject, please email editor@storm-asia.com with your details and a short summary.