FROM THE brilliance of invention, mankind has plunged into the depths of soulless materialism. What can we do to exit the dark and enter the light?

For many years now we have sat in thrall as a barrage of gadgets have hit the market promising to change the way we live. While marvelling at the slick aesthetics and functionality, I end up thinking that we haven’t progressed very far at all. The Internet, Kindle and smart phones all represent speed and convenience but are they genuinely new?

For many they are simply a faster way of disseminating scandal, gossip and porn.

Mark Kurlansky, the acclaimed journalist and international bestselling author of books like Cod and Salt writes poignantly about this in his book 1968: The Year that Rocked The World. In this authoritative tome, Kurlansky discusses the German philosopher and political theorist Herbert Marcus who warned that technology would imprison people in unoriginal lives devoid of creative thinking and anesthetised into a complacency that would be mistaken for happiness.

Far from any authentic happiness, we seem to flounder from crisis to crisis — from the threat of terrorism, the Global Financial Crisis, the European Debt Crisis, the Nuclear Crisis in Japan, the US Debt Ceiling Crisis and back to the riots in Greece and the spectre of governments that can’t afford to govern. And that’s not even touching on the slew of natural disasters that have been occurring with increasing frequency around the world.

Where are the genuine advances?

Up to the middle of the last century we saw the introduction of motor cars, air travel, washing machines, light bulbs, telephones, feature films and much more — inventions that early humans could not have conceived. There was genuine innovation.

By the 1950s, the human race held grand dreams for the future.

In the 1960s, hope and love, exploration and revolutionary ideas came to the fore. People dreamed of communicating not with any device, but through an evolved consciousness.

In fact, by then — the 1960s — we thought that by the turn of the century we would be on other planets, with space travel a reality and time travel a possibility.

Aircraft today are certainly faster and bigger but they are not new. Today’s phones are vastly more functional but hardly new. And today, here we are, still bound by our crude physical bodies and our cruder mechanical and electronic devices.

We still have not figured out how to tap into our collective consciousness or explore different realities. Coincidentally, in Frank Herbert’s 1965 award-winning science-fiction novel, Dune, evolution is inversely related to the relinquishing of technology — based on an understanding that real progress does not take place in the material world.

Of course, it is true that there is brain exploration, but the numbers interested in this are so small as to be irrelevant. In the meantime, we are developing more and more allergies, cancer continues on its deadly rampage and mental illness has emerged as one of today’s biggest global health concerns.

It’s not overstating things to say that the end of NASA’s manned flights to outer space signalled the death of real ambition for the advancement of the human race. Our cosmic exploration, at its zenith in the 1960s, represented a rare moment in history.

When else have we said — and meant it — that we would put all our resources, intellect and hopes behind achieving something so grand, something out among the stars?

Looking Up For Inspiration

How long since we held our collective breath and looked on with universal expectation to the heavens, as we did when we watched Neil Armstrong take the first recorded step on the Moon?

It was an event which captured our imagination, an event for which we all cheered. We watched and saw humanity advancing, exploring and pushing its boundaries. This mood of pioneering exploration peaked again with NASA’s shuttle programme and the hope that one day all of us might explore the universe.

It was an event which captured our imagination, an event for which we all cheered. We watched and saw humanity advancing, exploring and pushing its boundaries. This mood of pioneering exploration peaked again with NASA’s shuttle programme and the hope that one day all of us might explore the universe.

This may never happen again. Entrepreneurs and the private sector can’t do this. Only nations can mobilise all that’s required to go beyond our current limits.

You might also want to read:

Trump — The Dawn Of A Dark Age

So, what defines us now?

If we look at film and television there is a dearth of original ideas. Green Lantern, Footloose, Captain America, Batman, Spiderman, Superman, Charlie’s Angels, Dukes of Hazard, Hawaii Five-O, Planet of the Apes, Arthur, Karate Kid, Conan the Barbarian and so on.

All remakes, just as so much of today’s music is. Original thought, it seems, is hard to come by, and new ideas are in short supply.

Of course our current times are not all dark but neither was the period between the fall of the Roman Empire and the Renaissance without artistic and intellectual accomplishment. But in comparison — to the time before and after what we commonly refer to as the Dark Ages — there was a paucity of creativity and original thinking.

Today too, there is genuinely creative output, like the movies Days Of Heaven and The Tree Of Life, both by Terrance Malik — but the overall atmosphere is of rehashed ideas. There’s a pall that hangs over us. So while Malik clearly makes great films, he isn’t inventing a new medium or standing at the vanguard of a new art form. And while the good people of Apple make great communication devices, they certainly didn’t give birth to the telephone.

Another Darkness Cometh

I believe that 1970 marked the start of our current Dark Age. Sure there was some great art in the early ’70s. In fact, this is my favourite period of music and film. Think Harold & Maude, The Godfather, Chinatown, Sticky Fingers, Late For the Sky, Led Zeppelin IV, Ziggy Stardust. But the period betrays a definite reaction to the optimism and largesse of the ’60s.

The early ’70s was stripped back, without the boundlessness of the previous decade, without the big ideas. Artists seemed to be closing down and looking inward. In the words of my favourite singer of the time, Neil Young, this period seemed to be “after the gold rush”. Before 1970 there was such optimism. There had been a social and justice revolution — black rights and women’s rights — and so many of the accepted paradigms were questioned. Almost forgotten now, Robert Kennedy questioned the logic of economic growth when he said:

“We will find neither national purpose nor personal satisfaction in a mere continuation of economic progress, in an endless amassing of worldly goods. We cannot measure…national achievement by the Gross National Product. For the GNP includes air pollution…it counts special locks for our doors and jails for the people who break them. The GNP includes the destruction of the Redwoods and the death of Lake Superior. It grows with the production of napalm and missiles and nuclear warheads…it does not allow for the health of our families, the quality of their education, or the joy of their play…the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials… the GNP measures neither our wit, nor our courage, neither our wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion nor our devotion to country.

“It measures everything, in short, except that which makes life worthwhile.”

In fact, the use of such measures as GNP and GDP has in recent times come under scrutiny in many countries, with leaders acknowledging the inherent shortfalls of using them to determine accurately how contented people are.

The Rolling Stones free concert at the Altamont Speedway in California in December 1969 was a harbinger of the menace and violence which awaited Western society. Rolling Stone magazine described it as “rock and roll’s all-time worst day, December 6th, a day when everything went perfectly wrong”. Altamont, where security was provided by the violent Hells Angels, saw at least one murder and countless beatings.

Ironically, it took place only four months after the universal brotherhood of Woodstock.

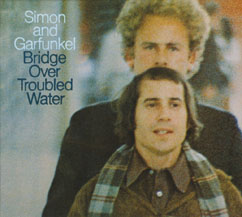

By the time Simon & Garfunkel released their last studio recording, Bridge Over Troubled Water, the following month in January 1970, the world had moved into a darker, more cynical period. It was as if Simon & Garfunkel were bearing witness to the death of love and peace, of humanity and equality, abandoned in favour of pragmatism, expediency, reactionism and conservatism — all precursors of the economic and business paradigm of today.

the death of love and peace, of humanity and equality, abandoned in favour of pragmatism, expediency, reactionism and conservatism — all precursors of the economic and business paradigm of today.

We became far less tolerant and bred fundamentalism. Unfortunately for creativity, business is process-driven, controlled and highly regulated. Business and its organising frameworks of the market and corporations are poor places from which to evolve. When the dominant paradigm and pursuit is business, we are in a poor place from which to innovate and grow.

Art Challenges The Norms

The best art, on the other hand, is confronting, and challenges us to think about our lives differently; it questions our norms and beliefs. Artists once felt a responsibility to imagine a better world and reveal what it could be. Art can elevate us and move us. From here we can feel connection, joy, love.

Business simply can’t do this. It can’t make us hope and dream — it’s not what shareholders demand.

In more prosperous times, wealthy merchants patronised artists because they could give us beauty. But in a world where beauty has been relegated, there seems little drive to give to those who can create it. Likewise, we once believed in our scientists for they promised a better future. Now they are derided and starved of funding.

In fact, only a few years ago 120 Nobel Laureates and 1,600 leading scientist implored the world’s powers to act on climate change, only to be largely ignored. An issue exacerbated to a much larger extent by US President Donald Trump’s recent actions with regard to the matter, by his finite wisdom on the matter. If we don’t listen to the smartest and most experienced scientists, those who are experts in their field, then we are in real trouble.

Today, on the whole, life is more cautious, closed and fearful. Without question there is a waning of education and reason, a move to legitimise torture in the name of defending security, the rise of religious fundamentalism and a worldwide cult of celebrity. These are emblematic of a dark time. It is certainly also the case that today’s youth are the ones most scared about the future of the planet. They are again waiting for the great leap forward. But instead, we have race riots in Britain and violence in many parts of the world.

They represent the now. Whenever you think about science fiction dystopias, those novels or films set in the future, they look a lot like the dark, burning, violent scenes that flashed across our TV screens back in August.

Blade Runner, the iconic film of 1982 has this overall feeling of darkness. That’s how science fiction writers saw the future. The only problem is that it looks a lot like today. The movie was, in fact, set in 2019, a few years from now and all too possible except for the flying cars. The closest we’ll get to that would be autonomous cars…maybe.

What Drives Us?

Today, fear seems to be the underlying motivation and the overriding human experience. The relentless rounds of natural disasters around the world have also eroded our sense of certainty and control and perhaps, our hope for the future. Likewise, so has the Global Financial Crisis and its seven million victims of job loss in Asia alone.

Where is the unbridled optimism and hope of 1968 as we raced towards the Moon, righted the wrongs of racial injustice, marched on the long road to redress the balance between men and women and questioned the gulf between economic privilege and life-sapping poverty? Where is that sense that anything is possible, the feeling that we are on the cusp of greatness as a species. Instead, in the two most populous — and soon to be most powerful — nations on earth we have hundreds of millions of people in abject poverty, more than ever before in absolute terms despite the record number in the new middle-class. What’s more, the yawning chasm between rich and poor continues to widen and at greater speed.

I’m open to the possibility that life is richer and more progressive than I have portrayed. I genuinely hope I’m wrong in my assessment. If the future is brighter than I have painted it, then I will rejoice. In the meantime, how do we break out of this Dark Age that I have described? How can we cultivate innovation and creativity? How can we help ensure that we are ready to deal with problems that are as yet unimaginable?

What to do?

Here’s what I feel we must do. We must question our faith in a free-market paradigm that exacerbates the divide between rich and poor. We must challenge the need to fill every waking moment, and leave empty space for reflection and contemplation, which are the catalysts for creativity.

We must promote more women to positions of leadership and influence for this will engender long-term thinking and more collaborative decision making. We must introduce the study and practice of positive psychology into our schools and workplaces for this will cultivate a greater sense of wellbeing.

We must also question the amount of killing that humans carry out every day on millions of cows, lambs, pigs, ducks, hens, chickens, fish, crustaceans, deer, whales and people. What if we dedicated an hour to not killing? This might raise awareness of our actions and set in motion the possibility of change, for advancing our relationship with the planet. Just one hour when humans decide not to kill. How might this change our consciousness? Surely it is worth finding out.

This article was first published in STORM in 2012, but has been updated.

Main Image: Stone36 / Shutterstock.com