FROM a bad student to a record-breaking artist, Tan Swie Hian has let nothing fetter his imagination. From poems to philosophy, sculpture to art, this gifted septuagenarian still burns with the fire of creativity.

It was a nature versus nurture discussion at Tan Swie Hian’s airy studio in the converted school in Telok Kurau.

The various classrooms have been taken over by artists who have filled their studios with the tools of their trade, while scratching their names on the doorjambs or hanging little signs announcing the occupant’s name.

Beneath a whirring fan that stirs the humid air, the Singapore Cultural Medallion winner sits cross-legged on the floor in shorts and paint-splattered shirt as he expounds upon his latest creation — The Swing Is Her Only Flight; Homage to Leonor Fini (2014).

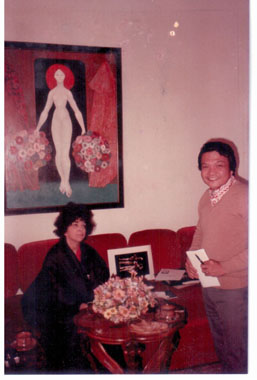

The idea for this piece was planted during a 1982 interview with the Argentine artist, considered one of the most significant women artists of the mid-20th century. The journal in which that interview was recorded was buried under a pile of other journals, diaries and materials that Swie Hian had accumulated over time. It was a fire in a nearby atelier, in 2013, which led to its rediscovery.

Like a phoenix from the ashes of that damaging fire, the journal was found, and this vivid painting emerged, in acrylic on canvas.

The celebrated, multidisciplinary artist is not prolific in his output, so there is already a queue of potential buyers for the large and colourful work, a result of a three-week flurry of activity. Swie Hian, however, wants to showcase this piece for a while before it is likely to be cosseted in someone’s private collection.

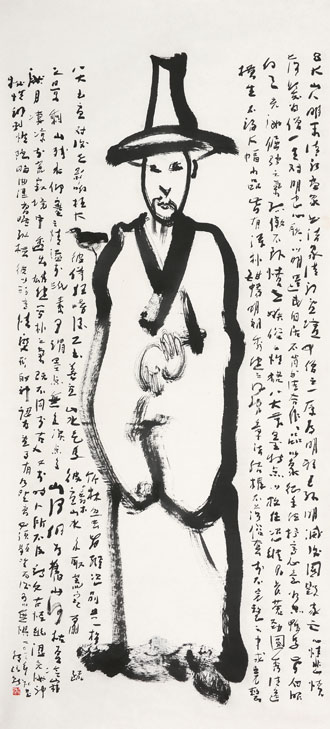

Fresh from the record-breaking auction of Bada Shanren which was acquired by a Chinese collector for S$4.4 million, Swie Hian is philosophical about this latest feather in his colourful and well-decorated hat.

Could this perhaps be the key that unlocks Asean talent to a global audience?

It’s a case of nature and nurture, he reckons.

The erudite artist offers poignant glimpses into local art and his role in it.

On being the most expensive artist in Southeast Asia:

“A people will be culturally awakened only after they are well clad and well fed. We started actively building our cultural hardware since the 1989 Report of the Advisory Council on Culture and the Arts.

“Culturally, we used to drag behind most of our ASEAN neighbours. It was the contemporary Philippine and Indonesian artists who held the records for the highest-paid artworks at auctions.

“However, in 2012, in Beijing, my oil and acrylic painting When The Moon Is Orbed was sold for S$3.7 million, setting a record for a living artist in Singapore as well as in Southeast Asia.

“And in November 2014, I broke my own record when my ink painting Bada Shanren sold for S$4.4 million.

“For once, since Raffles, we are in the lead.

“It is without any doubt a leap forward. But compared with the achievements of the big boys in the contemporary Chinese art circles, for instance, it is still a far cry, and with those in the West, the gap is still incredibly wide.

“Anyway, according to the findings of a Swiss bank, the number of artists who could command a price ranging from US$100,000 to millions of dollars constitute only 0.16% of the talent available worldwide. I am lucky to be within this bracket.”

On being a bad student who turned good:

“In 1962, as I was emotionally upset, I could not concentrate on my studies. I cheated in a History exam and was caught and severely disciplined, and almost expelled from the Chinese High School.

“Then, an awakening dawned on me when my brother committed suicide, hurting my beloved mother to the core.

“I vowed to be good.

“Following the care, love and teachings of the Chinese and English teachers of both Secondary Four (where I repeated), and the Upper Secondary One and Two, I eventually became one of the top students in the school, and among the three students chosen by the school to be interviewed by Time magazine.

Late growers have no reasons to be down. When one regains the memory, one can sing again the song from his heart.”

On the possible emergence of another Tan Swie Hian:

“After a high-ranking government official read an interview with me, conducted by Pan Cheng Lui, a renowned poet/writer/editor, he asked Pan how could Singapore produce another Tan Swie Hian.

“Pan pointed to the ceiling saying that it is first of all up to ‘upstairs’ to decide if another Tan Swie Hian would be planted here, and, secondly, it takes a French Embassy where Tan Swie Hian was groomed for 24 years to come into play. Pan pointed out that it was French Ambassador Marcel Flory who opened Tan’s first exhibition in 1973 and wrote the preface to the catalogue. Tan’s French colleagues almost bought up all the works of his first exhibition and wrote extensive analyses and criticisms on his works.

“And France has showered Tan with the greatest number of awards and honours.

“Thirdly, it needs, of course, the land of Singapore to forever nourish him.”

This article was originally published in STORM v.22 December 2014