SINGAPORE’S wealth is evident in the bulging pockets of some, but not reflected across society.

Credit Suisse Research Institute’s (CSRI) annual wealth report for 2016, released late last year, lists Singapore as the wealthiest nation per capita in the Asia region.

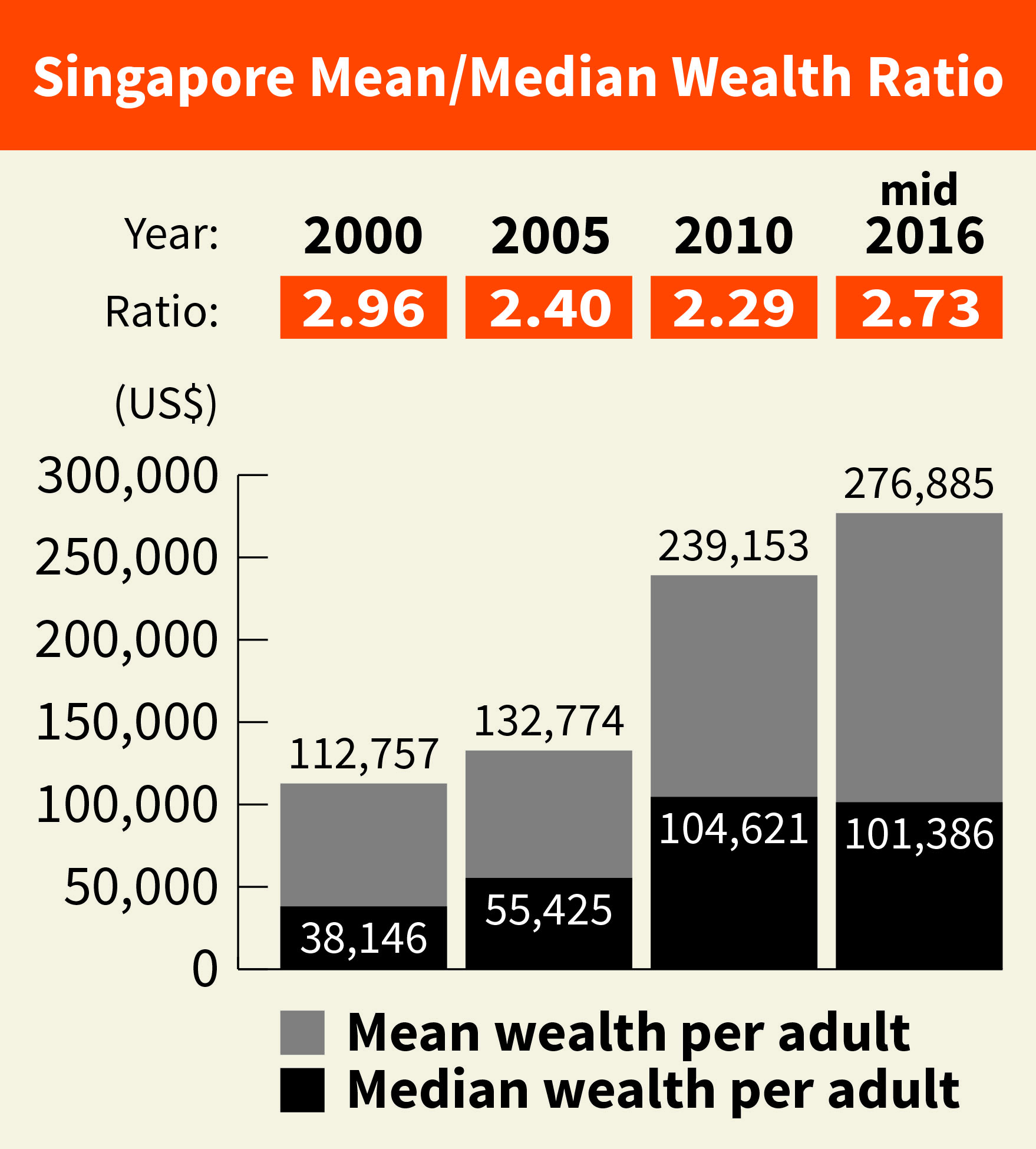

The city-state’s adult population had an average wealth of US$276,885 (S$395,000) per person.

This ranks 10th in the world and should not come as a surprise as the city-state engages in its relentless pursuit of progress. It comes at a cost though, such as greenery and cemeteries making way for new infrastructure development. Preservation groups may make some noise, but they are usually toothless and too late.

When the powerful Urban Redevelopment Authority has its sights set on a new development, it ploughs through any obstacle. Singaporeans are used to it.

This can be partly attributed to the fact that wealth accumulation, a positive by-product of economic progress, has been cherished and well-received by Singaporeans since independence. So much so that expectations of continued economic expansion which leads to potentially further wealth accumulation is in the DNA of modern Singapore society. It underpins the mandate that Singaporeans have consistently given the government for decades.

The Growing Wealth Disparity

There is little or no recognition that people are effectively borrowing this wealth from future generations. The latter will be stuck with the bill, be it a 30-year mortgage loan, or rising education and healthcare costs.

While the average household wealth of US$276,885 per capita cited by CSRI in its wealth report looks and feels high, especially if you live in the heartlands as more than 80% of Singapore’s population do, a more accurate measure reveals the wealth disparity in the country.

Median wealth — which is the wealth owned by the middle person when all residents are lined up in order of ascending wealth — stood at US$101,386. The difference between the average and median wealth exposes the wealth gap in Singapore — the wealth of a small percentage of individuals pulls up the mean significantly, according to CSRI. Despite the overall accumulation of wealth, the gap between average and median wealth has expanded further in recent years (see chart).

Source: Credit Suisse Global Databook

Source: Credit Suisse Global Databook

Conditioned To Accept

Singaporeans are wired to believe that rising affluence is a positive consequence of the island’s progress. But in some developed countries, which are more mature in terms of the wealth cycle, this is being questioned.

Academics from the University of California, Berkeley have found that rising affluence seems to have negative consequences for society.

In research published in 2015, it was revealed that wealth and compassion have a counterintuitive relationship.

Wealthy people are found to be less generous, and less empathetic to their poorer cousins. While the rich give more money to charities, the proportions relative to their incomes are lower than for poorer people. They are also encouraged to do so for tax benefits.

The poorer in society also forge closer social bonds to combat adversities in life, which in turn make them more compassionate towards others. Although wealthy people do form social bonds, the academics found that these bonds rarely had economic consequences.

Dacher Keltner, who is a professor of psychology at the University and directs the Berkeley Social Interaction Lab, described the situation well when he wrote: “When you lack institutional support, when you face threats in life, the only way to survive your environment is to connect with other people. You reach out to people more. You form strong social ties. You need them, and they need you. When you’re poorer, you’re helping someone get to work if their car broke down, or looking after their child while they run to the store — and they’re doing the same for you. Humans have this wonderful ability to bond in the face of threat.”

You might also want to read:

Big Data Is The New Balance Sheet

Cash In The Bank Or Cash And Carry?

The Ugly Side Of Charity

The counterintuitive relationship between wealth and compassion is evident in Singapore. For instance, a report in The Straits Times in January this year highlighted “uncharitable” donations by the Singapore population. It was estimated that up to 40% of donations were discarded because they were unsuitable. Charity staff and volunteers have to expend time and effort sifting through donations and clearing away unsuitable items.

The Food Bank Singapore, which redirects non-perishable food items to social service organisations, estimated that 10%–20% of donations collected were thrown away. Expired, unsealed, half-consumed food items were often in the mix with donations.

At the Singapore Red Cross, about 30%–40% of public donations it receives do not make it to its thrift shops.

Emboldened by the anonymity that comes with making these donations, Singaporeans seem to have no qualms about indiscriminately disposing their unwanted items into the charity bin. This sort of behaviour could worsen with a technology-savvy younger generation who have many digital friends, but not as many face-to-face relationships. They tend to give little thought to those they perceive as lesser people than them in society.

Being affluent does not automatically endow a person with empathy. In Singapore, it seems to be heading in the opposite direction. Gracious acts should not only happen when people are being observed. They have greater impact when such acts are unseen, unpublicised and anonymous. That is real wealth.

Thus It Was Unboxed by One-Five-Four Analytics presents alternative angles to current events. Reach us at 154analytics@gmail.com