IN AN increasingly complex global business environment, the opportunities to rake in the returns beyond one’s shores are often fraught with potential risks.

In conducting global business, the importance of knowledge and boots on the ground are vital in helping to minimise the downside to any endeavour. While businesses continue to look towards larger markets, there is always the chance that things may not go well. Many will follow along paths already beaten down by others, while some will steer clear of challenging situations. The ultimate decision is still in the hands of the risk-taker. But armed with more knowledge and an understanding of how the various pieces come together in a foreign land will help them navigate challenging waters.

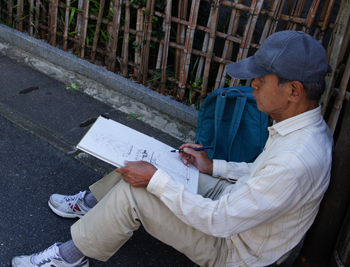

Tadashi Kageyama learnt firsthand about the changing world. Born in Japan, he grew up in Europe, America and Latin America, courtesy of his father’s role in the foreign service. He came from a generation that was curious about the world and how the various pieces fit together, something he finds lacking in today’s Japanese youth.

As Head of Kroll’s Asia Pacific Practice, Senior Managing Director Tadashi travels extensively to meet with clients facing issues in a variety of challenging areas.

STORM: How should business leaders prepare themselves for risk in today’s volatile environment?

TADASHI KAGEYAMA: After the Lehman Brothers shock in 2007 our business also went down, but we noticed that soon after, many of the financial institutions were back to paying out big bonuses and engaging in sophisticated financial transactions and still conducting high-risk investments. The cycles have become so short, people are asking for results in such a short time.

But I have learnt from working with several bankers that many of them don’t care. They like to hear what they want to hear, so they can put up the proposals to their investment committees signed and sealed.

And then they put it up on the market and it multiplies and they cash in. I’m not saying all bankers are like that, but I have seen some behave like that.

These are dangerous times.

We approach risk in a fundamental way. If a client is investing in a business, we try to understand who runs it, what do they do? Who are their customers? Are they conducting business ethically? We want the client to understand that there are benefits to engaging in sustainable business practices. When I look at a business, I want to see if it’s sustainable. If I put in the money will it run for 10 years, and not just for one year?

STORM: Isn’t it almost an expectation now for businesses to have quick returns?

TADASHI: It is and I’m probably the minority trying to fight this with the management. Don’t get me wrong. I like to see fast growth. But you can only do so by keeping your house in order, making sure you deliver quality service. Double-digit growth is possible, but not for 10 consecutive years. Maybe for one year, and then you actually put on the brakes and look back and see if the business activities are sustainable.

In my view, a little over GDP growth or the Consumer Price Index would probably be

healthy. You should not expect 20–30% year-on-year growth; that becomes dangerous. People start to do things that are very creative when you are forced to grow that fast.

We observe this at fraud scenes a lot. People will do funny things to ensure that it keeps growing on the books.

STORM: What are some of these “funny” things?

TADASHI: Typical ones like cooking the books, circular Ponzi schemes and fictitious sales. There’s a variety of ways of doing this.

I’ve been doing this for more than 14 years and I’ve not seen any perpetrator who I’d give a prize for innovative deceit. What makes things difficult is when the perpetrator is committing fraud not for their own benefit, but for the company’s benefit. That becomes really tricky.

For example, if there’s a manager who brings in his family into the supply chain and makes a lot of money and he gets a cut, we would consider this a conflict of interest transaction. You know their motivation is to make a profit. But there are people who bring in friends into the company and are providing services and goods at fair prices, and they don’t take any cuts. And they genuinely believe they are doing something good. He’s bringing in someone he trusts to do a good job. Problem is, if you leave it as it is, people will start to manipulate the system for personal gain.

When I investigated a 50-strong sales team that sold equipment for hospitals in South Korea, we found that 45 of them were paying bribes to hospital personnel and health ministry officials to sell their equipment. This is a crime. It is corruption, and so the decision was simple. They should be fired. We also found out that none of the 45 people benefitted from this fraud.

Some of them said in tears: “I did this to save our business because the competitors are doing this. I know there’s a code of conduct, which is why we didn’t ask the company for bribery money, we manipulated our expenses so we could claim more money and use this money to pay them.”

Many people engage in fraud without knowing that it is fraud. They will do anything to meet a financial goal. You need to set realistic targets and timeframes, and provide the right resources for people to achieve those targets. Otherwise, if you keep pushing, people will start to become too creative.

STORM: In today’s complicated and networked environment, what is the right or wrong decision?

TADASHI: This “right or wrong” question is a difficult one to answer.

The ultimate motivation of a company is to make profit. These days, it’s to make profit ethically, and integrity has become very important. I feel this is largely due to the expansion of the Internet and social media. When I started in 1999, the Internet wasn’t as expansive as it is today. Back then, when companies thought of stakeholders, it usually meant their shareholders, employees, customers and suppliers, and usually government regulators.

Today, in addition to these stakeholders, the big factor is society. Someone who is not a stakeholder is interested in what the CEO says, and what the company did as he or she is keenly aware of what’s happening in the world.

I say to the management, it’s important to meet the financial targets, and to be compliant. These are often “yes” or “no” questions. Typically, the management needs to understand these rules so they compete within the rules of law. But sometimes, they will still get into trouble. Sometimes it’s not a violation of a law.

It just looks very bad.

When the client receives a complaint letter about a product made in Bangladesh by children, we investigate and find it’s true. The garment company did not know about this because they sub-contracted it to an OEM manufacturer who claims to comply with international labour regulations. So the company feels it’s done its due diligence. Are we liable? Maybe, maybe not. But that’s not the issue. Your customers now see your brand and product as the result of slavery.

It’s quite astonishing that CEOs sit behind their mahogany desks and ask what law they are violating. Social compliance is a difficult thing to manage. Leaders need to be aware of what society is saying.

STORM: How do virtual rules for the Internet impact decision making?

TADASHI: The founders of Kroll told me that in the early days it was easy to do business. If we had people in remote locations we had business. People didn’t even have fax machines then. Then came the Internet. That was a major trigger for change. Simply having a Kroll person in Zurich to do an investigation wasn’t good enough.

And then the social network services changed the world. But we thought the Internet would make our business more difficult because the value of the information would become cheaper and more available. But the businesses are saying that since there’s so much information in cyberspace and in the public domain, they need more effort to weed out the unreliable information. Our folks spend more time doing that now.

How we source information has changed. Before we had to go to a location to get information. Now there’s a lot that can be sourced in the public domain. At the same time, we need to isolate the erroneous information; which requires a new set of skills. I always tell my daughters not to use these services as far as possible. If you have to, then consider it public information. Though we’ve had some interesting cases when it comes to find a missing person. Social network services have been useful in locating missing suspects, or identifying hidden aspects, because people cannot keep quiet.

You might also want to read:

5 Facts About Selling The Family Business

STORM: What’s the sentiment about Japan?

TADASHI: One in four Japanese is aged 60 and above. You cannot expect people in their 60s and above to spend as much as those in the 30–40 age band. Unless the Japanese government changes completely and brings in foreign workers, only then will the population demographics change. Neither party is inclined to do this, however. Since Prime Minister Abe’s economic stimulus has worked so far, the indexes are faring well, and there is the Tokyo Olympics to look forward to in 2020. My concern is that since we are back on track, the companies that have gone global may say, why spend so much energy outside of Japan when we can make money in Japan again?

TADASHI: One in four Japanese is aged 60 and above. You cannot expect people in their 60s and above to spend as much as those in the 30–40 age band. Unless the Japanese government changes completely and brings in foreign workers, only then will the population demographics change. Neither party is inclined to do this, however. Since Prime Minister Abe’s economic stimulus has worked so far, the indexes are faring well, and there is the Tokyo Olympics to look forward to in 2020. My concern is that since we are back on track, the companies that have gone global may say, why spend so much energy outside of Japan when we can make money in Japan again?

If you study these big Japanese global companies, you see that significant profits still come from the domestic Japanese market. I hope the Japanese companies continue to go global.

Investment into Japan is limited, and certainly not at the level of early 2000s. There was a lot of activity when the government pushed banks to get rid of non-performing loans, and foreign firms came in and acquired them. Then came the Lehman shock, so the economy took a beating again. There was no investment activity. Then the 2011 earthquake deterred foreign investors.

These factors and the strong Yen, have driven Japanese companies to go outside. The country in the last 20 years grew less than 2% so people called that a recession. But if you go to Japan, you wonder where the recession is. The debt ratio is high, which is still of some concern, but the companies are still cash rich.

Japan and China have been under tremendous tension for the past few years because of the territorial dispute. So lots of Japanese companies have thought of shutting down operations in China and are thinking of moving operations to Southeast Asia. That is driving capital from Tokyo to this part of the world. That’s not all, there’s a fundamental change in China as well.

In the past decade the cost went up so fast annually, the consumer price shot up 9–10%. So, just sitting in China the costs go up 10% or more. People look at the costs and think it might be cheaper to make it in Okinawa.

STORM: How will the Olympic affect Japan’s property sector?

TADASHI: After the first Olympics in Tokyo, in 1964, the property values went up. But that was a different time. It was a time of the heavy industries and Japan was a factory nation. Japan of the ’60s and ’70s had the role of today’s China. In the ’80s it was Taiwan and Korea. Now they are moving production facilities to Vietnam and Africa. Every company is moving from expensive to cheap resources due to fast growth.

After the 2020 Olympics, I’m hoping the sustainable growth will continue for Japan. But the fundamental thing is Japan needs to have a greater inflow of people. To do that there needs to be changes to education. If you go to Japan it’s still very unfriendly; it’s hard to get around. For hundreds of years, Japan never had interaction even with its Asian neighbours. The government had no incentive to open up. Now that is hitting hard. The world is smaller and flatter, people doing business in Japan do not have to live in Japan.

That helped the Japanese recognise they are part of a global community. But people are still thinking locally. Even the younger generation. Every year the number of students going abroad to study is declining. Another disturbing phenomenon is they don’t want to work overseas. Even if they join the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, they want to work in Tokyo. This is concerning. They only see Japan as their domain of activity.

STORM: What do you look for when investing in Japan?

TADASHI: Japan needs to encourage big businesses to let go of some of the non-essential parts of business. They need to change laws to make mergers and acquisitions easier. Companies need to think differently. People still think good company equals big company, big company equals more revenue, more revenue equals a lot of employees. That was probably true until the late ’80s. Today, a good company might be simply a profitably run business that would attract foreign businesses to want to tie up with local businesses.

This article was originally published in STORM in 2014.