ARE OUR ties with our past still strong? Will our heritage straddle generations?

For a small nation, barely past the half-century mark, many would argue we are still in the process of building a national heritage.

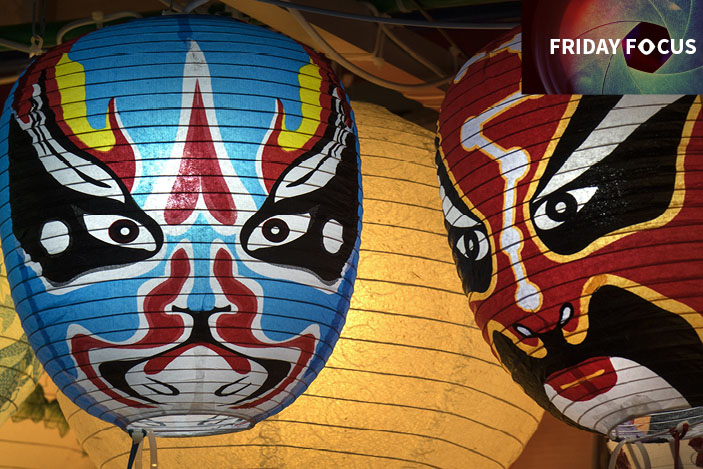

But as the Singapore Heritage Festival draws to a close — with events at the predictable historic areas like Chinatown, Little India, and Kampong Glam, and the Singapore River — it becomes clear that much of Singapore’s heritage is still deeply entrenched in its immigrant roots.

Our ancestral roots — Cantonese, Teochew, Hainanese, Javanese, Bugis, Nyonya, Tamil, Malayalee, Sindhi, to name just a few — the cultures and peoples that multi-racial Singapore is made up of, seems very much alive.

While heritage is kept alive in these little ethnic bubbles, we must now look forward to the future and the next generation to carry the torch that could light the way for a heritage that flows from new generations of migrants weaving into the current fabric of society.

Pioneer Singaporeans are quick to talk about community, their links to cultural roots, the kampong spirit, and coming together as a people in the face of the great adversities of the past. But as they try their level best to pass on these stories and traditions of a very different nation, it is critical to understand how much value heritage holds for the next generation.

Will the stories, traditions, practices, and even artefacts and heirlooms, often passed down generation upon generation become lost to us in years to come?

In this week’s Friday Focus, we speak to Millenials to find out what heritage means to them. We also speak with Prof Kwok Kian Woon, the former President of the Singapore Heritage Society to get his views on the topic.

Prof. Kwok Kian Woon Anthony, Associate Provost of NTU (Sociology), and Former President of the Singapore Heritage Society on the challenges we face in building heritage in Singapore.

Heritage is simply defined as the “living presence of the past” i.e. how aspects of the past continue to have a meaning in our everyday lives.

In that sense and looking towards our next generation, we have to first ask if our youth have a sense of family history — knowledge about their grandparents and great grandparents, their lives and experiences, and those periods in history.

This is always a good start — start from yourself, then gradually become curious about the histories of your friends, who do not share the same background, or even from other ethnic groups.

How successful are we in doing this?

It’s hard to say because this is not a top–down process but something which people themselves must take ownership of.

Most importantly, heritage is not something that comes from external sources. It has to come with your own questioning about who you are and where you come from. Then you delve deeper into the people around you and society at large.

This is where curiosity becomes essential.

There is a lot of “living presence of the past” around us, but if we are not searching, curious, and aware, they don’t become part of our everyday lives and we lose something.

But it is not without challenges.

Rapid social transformation — neighbourhoods have moved or transformed, and continue to do so, through constant urban development.

The changes to our languages — can the different generation still communicate in a common tongue to pass on these stories?

However, I notice a new emphasis on “intangible cultural heritage” (to distinguish from that which is “built heritage”) — like our myths, legends, stories, practices, and certain wisdoms on how we relate to other people.

I don’t think our modernization has totally erased our intangible cultural heritage. They are for us to recover and rediscover and that itself can be quite a meaningful and exciting journey!

Thankfully, the Millennials believe heritage is important.

“Without the old, we will not have the new.” —Nur Rashidah, 25

“It’s a part of me. It’s very ignorant to not know.” — Cristie Kennedy, 23

Knowing our roots is key to make any progress. As emphasized in a Chinese proverb: “To be thankful for all the elements and processes, both past and present, that allows one to enjoy a humble cup of water.” — Chow Zi Xin, 18

We view heritage differently because we come from different backgrounds.

Andre Andika has a mixed heritage. His father is of the seafaring Bugis stock, while his mother is a Nyonya. He confesses to being more aware about the Peranakan heritage as opposed to the Bugis heritage because his father rarely talks about the “mysterious pirates of the sea”.

“I look forward to inheriting the family kris from my father. ” — Andre Andika, 27

The kris, a curved dagger of Malay origin, is a family heirloom that is passed down from generation to generation.

Similarly, the stone pestle and mortar is an artefact of great importance for Nur Rashidah’s family. The traditional grinding device is the foundation for all their sambal belacan recipes.

“It was passed down from my great grandmother, and my family swears by it. It is still used in the kitchen today!” — Nur Rashidah, 25

All our histories come together to form a nation and its heritage.

To Diana Bakar, 21, national heritage is about obtaining and accumulating knowledge. Not everybody’s ancestors were heroes in the war. Their heritage takes the form of a national narrative — the cuisines, national holidays, and of things that everyone deems Singaporean.

Tharani Nadarajah, 21, remarked that within her family, they have their own values and practices, and they co-exist with the heritage of the country.

Besides being Singaporean, Laveena Vaswani, 23, owns another collective heritage passed down from her Sindhi ancestors. Her grandmother lived along the borders of Pakistan and India, partitioned, and ruined during the independence of Pakistan in 1947. “The places no longer exist and people have moved.”

In Vaswani’s case, there is a blurring of the distinction between personal and collective heritage — the diaspora contributed to the history of the Sindhi community and at the same time, left a mark on the family line. This narrative from her family combines with that of other Singaporeans to form a collective Singapore heritage.

While many weren’t apathetic towards Singapore’s heritage, none we spoke to were enthusiastic about it either.

Chow Zi Xin explains that “it would be disappointing” to not know Singapore’s history and heritage. She feels that the knowledge of Singapore’s (and her own) roots is integral to being Singaporean. “But, there are other things to worry about,” she concedes.

“In the age of globalization, change is constant,” says Diana Bakar. And reflecting on the heritage areas in Singapore, she suggests that there are more important uses for the spaces, especially in land-scarce Singapore. “Although heritage is important, it should not get in the way of development.”

Will progress and globalisation erode Singapore’s heritage?

Nur Aisyah Rapid, 27, laments that Singapore is “too developed.”

“Everything is gone. There is nothing you can lean back on. It’s too fast-paced, making it almost impossible to build any heritage. There is nothing to start with so I don’t know what I can give to the future.”

Chew Min Hui, 20, has a similarly gloomy outlook: “We are quick in adapting to change, and maybe even too forward-looking. Heritage is often not as relevant, engaging or appealing compared to current events.”

Efforts to promote a Singaporean heritage are usually met with lukewarm response.

She attributes it to the closed-off nature of a ‘top-down’ approach to creating an ‘official heritage’ for the country. The government oversees classification and promotion of objects of heritage — such as historic districts and buildings that embody national values.

However, this excludes the populace in the creation of heritage and emphasises the notion that heritage can only be engaged with passively.

Heritage lacks a personal touch. It is merely knowledge acquired in an academic setting. And I think many from my generation would agree.

The formation of heritage and culture should be a natural process. It is more important to live for the values we believe in and celebrate the traditions we find meaningful. Only then, will the creation of an authentic heritage be possible.

BY S. Sakthivel, additional reporting by Chow Zi Fei

The Singapore Heritage Festival 2017 runs till 14 May. For more details, visit http://heritagefestival.sg.

[poll id=”47″]