IF you enjoy aggressive rollercoaster rides, you will be hooked on the takeoff and landing procedures on an aircraft carrier.

About two hours after taking off from Paya Lebar Airbase, the workhorse C-2A Greyhound is descending onto a small, moving patch about the size of six football fields in the South China Sea. The airmen are waving their arms to signal an impending arrested landing. It’s not as bad as it sounds, even if it is rather dramatic.

In the dimly lit cabin, the anticipation comes to a sharp halt as the plane hooks on to one of four flexible steel cables on the runway of the USS Theodore Roosevelt (TR) and goes from 250kph to 0kmh in just 3 seconds.

The two dozen passengers are thrown back in their seats — we fly facing the rear — and just as suddenly the pressure is off.

Even as we are getting over that abrupt tailhook landing, the rear door opens to reveal a hive of activity on the flight deck. As we climb out into the blinding sunshine, the sight of planes, helicopters, jets and predominantly men moving about purposefully is a lot of activity to take in, especially with goggles and headgear on.

South China Sea Tussles

The 20-storey aircraft carrier is moving at a third of its top speed of 55kmh in preparation of the training activities to take place in the South China Sea. Into its last month of a seven-month sojourn, “America’s Big Stick”, as the TR is referred to, is part of a mission to reinforce the US’ global presence.

The trillions of dollars of commercial seafaring trade that passes through the South China Sea must be reason enough for a few countries to establish their claims about who has rights over stretches of the 3.5 million square kilometres of water.

The mood in the South China Sea has always been tense with disputes over islands and maritime boundaries involving China, Taiwan, Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei, the Philippines and Vietnam.

The recent “incident” between the navies of China and Australia is just one of an ongoing series of assertions of the right to conduct freedom of navigation exercises in international waters.

Building Relationships

This was echoed by Rear Admiral Steve Koehler, Commander of Carrier Strike Group 9 (CSG9). “It’s an opportunity to show presence in the South China Sea and to interact with our allies and partners,” he said from the flag bridge.

Having come from the Arabian Gulf where the TR spent four months “countering specifically strikes and combat missions against ISIS in Iraq and Syria” the journey to Asia was to continue building on relationships with countries in the region.

Koehler has logged more than 3,700 hours in F-14 Tomcats and F-18 E/F Super Hornets on several combat missions. His personal decorations include the Defense Superior Service Medal and the Legion of Merit.

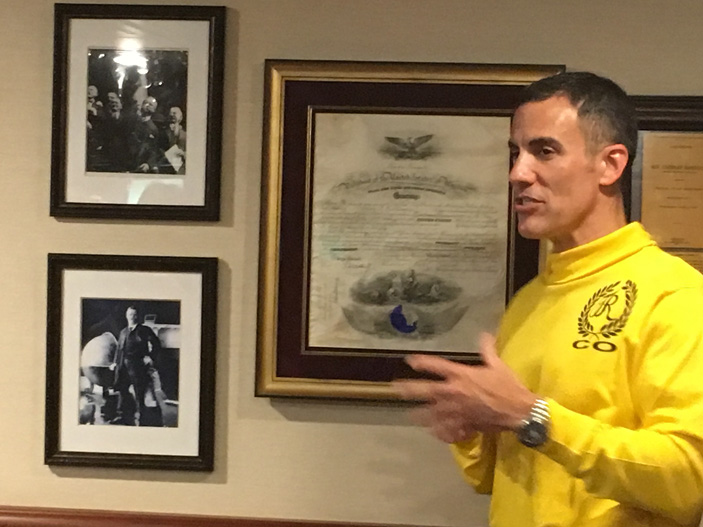

Commanding Officer Carlos Sardiello’s office — “the nicest room on board” according to Koehler — is done up to reflect the home of the 26th President of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt.

You Might Also Like To Read:

A Friendlier Traditional Circus

The memorabilia in this leather and wood-panelled room could have been transplanted from the President’s Sagamore Hill home in New York, and includes actual and replica letters, pictures and artefacts.

Prior to heading to the flight deck to watch jets take off and land, CO Sardiello talks about the crew and protocol onboard. As the man tasked with the welfare of the 5,000 people under his command and onboard, the much be-medalled Sardiello has ample chest room to pin them on.

“The crew on board is between 18 and 24. Exactly the same as it was 25 years ago. We think the youth are different but the same commitment to excellence and service is still the same,” he reinforces.

Sardiello participated in Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003, scoring the first and only strike by an S-3B Viking with an air-to-ground missile strike. He took command of America’s Big Stick in July 2017.

Flight Action

Watching my step and my head, I carefully climb up a number of near-vertical narrow metal ladders meant for the CO’s use before stepping out into a hive of activity on the flight deck.

Jets are lined up for takeoff and the ground is abuzz with crew members purposefully arranging equipment or waiting their turn to be engaged.

The horizon spans in all visible directions and the sea is way down there. Behind us is a big sign on the side of the “island”, basically warning us to be smart and follow the rules on deck.

The island is the tower on the flight deck, which allows the CO, Admiral and flight operations personnel to conduct proceedings. It is topped by a bunch of electronic equipment, radars, and antennae. But none of that is useful for our mobile phones since there’s no cellphone signal to be had. We’ve been cautioned to switch our phones to airplane mode since the search for a signal will drain the battery quite swiftly.

We are marshalled behind lines for our safety as the F18 jets let out little bursts of their potential — a deep rumble and a hint of a roar with a few waves of the flaps and it bullets off.

Sound And Fury

The takeoff blast is a roasting over and above what we are being handed in the blazing sun. It’s a full-on gust of heat, noise, smoke, and vibrations that can be both mesmerizing and terrifying. Especially in close quarters. Not quite within touching distance, but you certainly feel the presence of the planes as they take off 10m away.

Landing is another spectacle and we get to see what we experienced in the C-2A Greyhound, as the F18 swoops in to catch one of the 5cm-thick steel cables that will bring it to an abrupt stop. It’s effective and soon the jet is rolling off to one of the four large elevators that will bring it down to a lower level for maintenance work.

Catapulted Off

As we clamber aboard the Greyhound for the return journey, we are told we will be catapulted into the air. The airmen are busy waving again as we are hurled into the air.

This is the landing in reverse. From standstill, we are slung to 250kmh in three seconds. Only our seat restraints hold us back from doing a violent crunch sit up. The force of the take off is short but effectively sends us skyward for a droning journey back to terra firma.

Quick Facts

The USS Theodore Roosevelt (TR) was built over seven years and was commissioned in 1986.

It is a Nimitz-class, nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, capable of operating continuously for over 20 years. It is then refuelled and is able to function for another two decades. The TR was “refuelled” in 2009 and returned to action in 2015.

There are around 5,000 crew members aboard, of which around 20% are women.

There are around 70 aircraft on board and 300 pilots.

A Carrier Strike Group (CSG) consists of an aircraft carrier, cruisers, destroyers, a carrier wing of around 70 aircraft, and a crew of 7,500.

The Growing Role Of Technology

Does it take fewer people to operate with so many rounds of technology introduced to the USS Theodore Roosevelt?

“It’s different,” says Rear Admiral Steve Koehler.

“The size of this crew is about the same as when the USS Theodore Roosevelt was commissioned, in 1986. There is a certain amount of people you have to have. This ship has between 4,800 and 5000 people. There’s nobody I don’t need. If it could operate with 4,000 people I would,” he adds.

“If you look at the USS Gerald Ford, our newest aircraft carrier, it is designed differently — for a smaller crew size, thanks to technology.”