A ONCE common scene, coconut trees in Singapore are not found in abundance anymore.

Despite their prevalence in the past — dotting the coastline and a regular sight in the kampongs (villages) — they were seldom included in local Chinese ink art.

It was Chen Chong Swee, a teacher who incorporated local scenes in his works.

Chen’s Kampong Scene (1937) was one of the earliest ink paintings that depicted a typical seaside village scene; it was considered highly innovative then.

The coconut tree factored quite prominently in the local scenery, and their introduction immediately put context to the art.

The late artist’s work is on display at the National Gallery Singapore as part of a collection of 200 works by prominent 20th century artists who used Chinese ink as their medium of expression.

Alongside Strokes Of Life: The Art Of Chen Chong Swee are the works of the influential Wu Guanzhong: A Walk Through Nature. Rediscovering Treasures: Ink Art From The Xiu Hai Lou Collection delivers a comprehensive history of Chinese ink painting, as it showcases the art of various artists who worked in this medium.

Scarce Art

Just as the coconut trees have become scarce, so too are sightings of these masterly Chinese ink art pieces.

Many of these art works are in private collections, while some are in galleries. So, it’s a treat to be able to see such an extensive collection under one roof, and to explore how artists used the medium to illuminate life as it was in a time long before mass media helped to push messages through virtually and virally.

Chen’s eldest son, Tan Wee Lee, who was at the preview of the exhibition, says his father was one of the first artists to use the Chinese technique to paint coconut trees.

He recalled how his father’s strokes grew more confident over time.

“The first few times, he would need a few strokes to draw a tree. Over time, he would do it with a single stroke.”

Chen was also known for his prolific output. He would complete his works in one sitting. Some pieces took a couple of hours to complete, others around six hours, depending on the size and complexity.

Tan observed that his father wanted to paint to communicate. “He always believed art must be understood.” Chen reflected on key moments in history; not just the facts, but their implications.

On Deserted Fort (1948), Chen wrote a poem about the fall of Singapore during World War II and the lives lost during the Sook Ching massacre.

“The officers who surrendered have returned, unharmed, but the hate of ghosts remains to be exorcised.”

A general disdain for those who profit from the war machinery, it’s also a prescient sentiment about the ghosts of vanishing eras that, if not captured by the artists of the time, would be lost forever.

All three exhibitions will run till 4 December 2017 at the Wu Guanzhong Gallery and Level 4 Gallery, City Hall Wing, National Gallery Singapore.

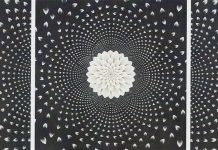

Main Image: Chen Chong Swee’s art: Thunderstorms In The South Seas; Landscape; Moonlight Scene At Kampong