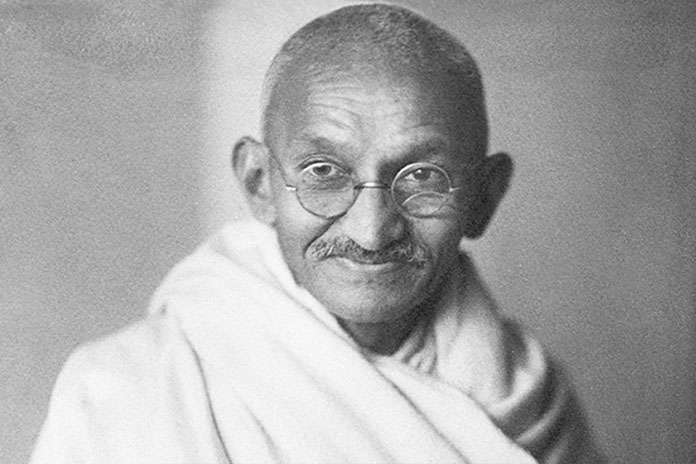

ON THE 150th anniversary of his birth, is Mahatma Gandhi’s position on non-violence still relevant?

While non-violence is often deemed a nobler option, it does have its limitations; the hope that your adversary is playing by the same rules, being one of them.

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi faced this conundrum squarely, always believing justice would prevail. In stark contrast to the violence displayed by the British in trying to strengthen their unwelcome hold on India, Gandhi’s approach was to choose the path of non-violent resistance. It eventually broke the shackles of British rule and inspired civil rights movements globally.

Non-violence may have its limitations, but in the long run the efforts will likely yield permanent solutions.

Gandhi’s preferred method of resistance was evident early on in his life as a newly-minted lawyer in India and, later, in South Africa.

In 1891, freshly returned from England after finishing his law studies, Gandhi had to face his own community, which banned foreign travel, with those doing so being excommunicated.

Although his relatives were willing to evade this prohibition, he didn’t encourage it since it was not in his grain to do something in secret that he would not do in public. He didn’t revolt against the ban either, nor did he try to seek readmission to the community.

He later wrote in his autobiography, “I have experienced nothing but affection and generosity from the general body of the section that still regards me as excommunicated. They have even helped me in my work, without ever expecting me to do anything for the caste. It is my conviction that all these good things are due to my non-resistance. Had I agitated for being admitted to the caste, had I attempted to divide it into more camps, had I provoked the caste men, they would surely have retaliated, and instead of steering clear of the storm, I should on arrival from England, have found myself in a whirlpool of agitation, and perhaps a party to dissimulation.”

Gandhi’s Lasting Legacy

During his time in South Africa, he coined the word “Satyagraha” (holding firmly to truth) adapting a winning entry for a competition he had organised to find a word representing non-violent struggle.

Gandhi was assassinated a year after India clawed back independence in 1947. Some seven decades on, the spirit of Satyagraha still holds sway globally to achieve political transitions or to make governments listen to people’s voices.

Nelson Mandela and Martin Luther King Jr, were two activists who fought for political and societal changes through peaceful means in their respective countries, South Africa and the USA.

The spirit of non-violence has seen the rise of people power who see solidarity in numbers. In the era of social media, stirring images of people moving in unison are shared globally and instantaneously, serving to encourage other nations to act.

The Arab Springs of the 2010s toppled leaders and forced regime changes through largely non-violent means. Arab Spring in turn, inspired the Occupy movements, a non-violent series of socio-political protests across the world, that fought against social and economic injustice.

During Occupy Wall Street, on 17 September 2011, protesters carried a statue of Gandhi on their shoulders to give expression to their non-violent protest.

The ripple effect of the Occupy movement spread so far and wide that at some point the movement was happening in over 80 countries.

However, not all the protests yielded desired results. Nor were all of them peaceful. Some did turn violent with the protesters reacting to the authorities’ measures.

Hong Kong would be a case in point where every weekend, demonstrators have been meeting and marching through public spaces to further their agenda for democracy, along the way disrupting public services and crippling some of the country’s key businesses.

But what became evident was that the generation after Gandhi did appreciate that non-violent protests, combined with deep political understanding and well-drawn strategies, could be an effective tool to make an impact on the authorities instead of resorting to violence.

Compassion And Conviction

Truth, non-violence and compassion were the basic principles that guided Gandhi in everything that he did. His entire political and social construct was built on these fundamentals. If non-violence is the means he adopted to make the English leave, compassion and empathy were the basis on which he approached social justice. He wanted India to evolve as an egalitarian society.

After Independence, the Indian government conceived of an exclusive ministry for the upliftment and welfare of the marginalised section of society. Although incidents of caste and religious differences do pop up in modern India, the country has witnessed the social ascendance of many people from the socially backward classes of the past.

Steven Pinker, author of Enlightenment Now, wrote that the modern world is a better place today where there are no wars anymore and where the constant deluge of innovations is making human life better.

While Pinker’s utopian world is still a figment of a fertile imagination, it’s true that countries generally don’t invade each other anymore for the sake of acquiring new territories or to settle scores.

However, the atmosphere of negativity and animosity that were triggers for past wars are still evident. They have morphed into different ways of violent expressions across the world. Battle lines are still drawn on simmering old hatreds — based on religious, cultural and ethnic differences. And individuals, rather than sovereign nations, take responsibility to set right the wrongs — perceived or real.

Divisive Lines Prevail

The world has changed significantly in other ways since Gandhi left. Many aspects of the modern world would have disturbed him. Although we live in an egalitarian society, religious/racial differences do rear their heads in pockets. Also, an aspiring milieu and a technological world has widened the gap between the rich and the poor. Sadly, the inequality of wealth today does not get as much attention as the inequality of the castes did in the past. In fact, the widening gap between the “haves” and the “have-nots” in a rich and tech-savvy world is creating its own set of issues that has evolved with the rise of technology and the digital divide.

On a wider map, globalisation of the nineties transformed the world into a melting pot with trade and culture cementing a relationship of nations. The idea was conceptualised on high ideals that trade among nations based on equality and friendship would promote global business.

But there are winds of change today across nations, where a sense of nationalism is gaining momentum.

To maintain dominance, or under the guise of protecting domestic economies, some countries are back-pedalling on what previous generations of leaders have set in place. The apple cart is about to be upset again, as the jockeying for power continues against a backdrop of issues ranging from rising population growth and sustainability of resources to global warming and economic overheating.

If we explore the transformations that the world has gone through over the decades after Gandhi, we would get a mixed bag of perceptions.

The world is more democratic today and people’s voices are more resonant now. But many of the other ideals that Gandhi valued besides non-violence, like simplicity, minimal living, and living in harmony with nature, and empathy for the poor seem to have been ignored by subsequent generations bent on leaving their own mark on a planet that suffers the consequences of their actions.

Aruna Srinivasan is an independent journalist based in Chennai. A Gandhi reader from childhood, she has always been trying to follow many of his ideals, even if Gandhi himself might not exactly agree with her statement.

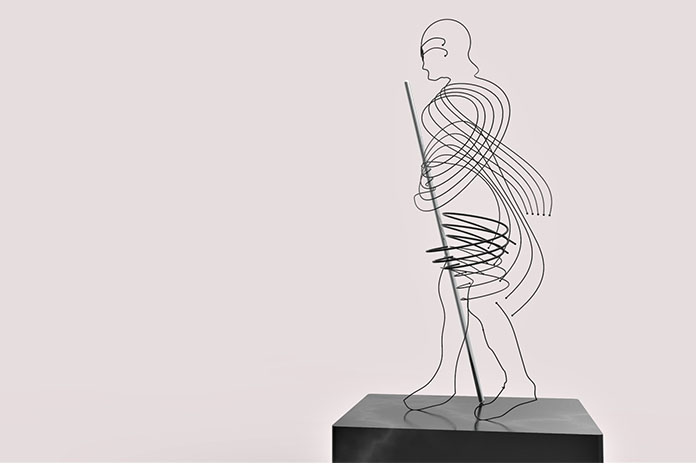

Kalyan S Rathore is a sculptor based in Bangalore, India. He likes to break down shapes into their building blocks and repetitive cells.