WHILE NOT wholeheartedly embraced by the mainstream art world, virtual art is steadily building its reputation, pixel by pixel.

The patterns repeat over a period of time; colourful amorphous hues that run across the screen, sometimes darting, sometimes drifting, but always mesmerizing in the constant, seemingly random motion that livens up the framed screen. While some may argue this could be a screensaver, a small community of tech-savvy artists is claiming the digital medium as their platform for conveying their craft.

At the entrance to Ikkan Art Gallery, Flower And Corpse Glitch unfolds as a modern take on an old Japanese tale about how deforestation will destroy the planet unless we step up to do something about it. The work is intricate and layered with old-style art animated to deliver a constantly evolving story that still plays out in real life.

Ikkan Sanada, an avid art collector and gallerist, sits in the sparse, Ikkan Art Gallery, located in an industrial building sandwiched by the containers in the port and noisy Keppel Road. Beyond, the now defunct railway station waits patiently for the train that will never arrive.

Ikkan occupies a small desk he shares with an associate, while on the wall, five screens, stacked atop each other in the dark room have water cascading down a rocky waterfall. From afar, Universe Of Water Particles appears quite lifelike as the water flows down the screens, but up close, that sense of realism gives way to a managed process; an ongoing attempt to humanise technology. There are a few long, unnatural lines, and that mist at the base just seems to sit there.

If you wanted that same waterfall in your home, Universe Of Water Particles would set you back around US$100,000. You would also have to splash for the five screens and the Mac Mini processors that power it up. But you would have the privilege of owning one of the six pieces of this virtual art piece that Japanese company teamLab has created.

Changing Artistic Landscapes

teamLab is not new to Singapore. Its work was included as part of a 2012 exhibition of significant new media, which opened the door to teamLab participating in the 2013 Singapore Biennale. It took four weeks to instal Peace Can Be Realized Even Without Order, in the Singapore Art Museum. In a dark, mirror-lined room, virtual dancers and musicians reacted to guests, and with each other. The S$1 million work used 68 computers and screens, and 34 projectors.

Ikkan Gallery represents teamLab, a Tokyo-based group of around 300 geeks with an average age of 27, who create websites, commercials and other mundane stuff for customers. A smaller group of 20 “ultra technologists” puts its collective ingenuity towards a variety of artistic pursuits — from moving images on screens to installation art and interactive pieces.

teamLab injects its creativity and curiosity into more commercial applications. It is currently working on a store concept in the Ginza area for an European department store, where an interactive floor will leave a trail of flowers. Its Connecting! Train Block uses projectors and sensors to link blocks that create connecting rails, road and flight paths for a virtual transportation network.

Art To Save Japan

It was Toshiyuki Inoko’s (picture at top) idea of rejuvenating Japan through technology that led to the formation of teamLab, in 2000, while he was studying Mathematical Engineering and Information Physics at the University of Tokyo. Inoko and his partners have probed overlapping areas where art, technology and society converge.

Ikkan reckons their art isn’t profitable, yet, given the amount of time spent in creating the works, but the quest is to push and test the boundaries of how art is defined. “Many people do not accept it as fine art,” he admits. “Most older people reject it, whereas those under 40 and the 30-somethings are positive about it.”

Digital art has existed since the 1970s under various guises. Computer art, multimedia art, new media art have at one time or another been digitally pushed into the artistic space. In recent years, acceptance by the established big boys of art, like the Tate Gallery, Museum Of Modern Art (MOMA) and the Getty Foundation, has given more credibility to the medium.

Digital art has existed since the 1970s under various guises. Computer art, multimedia art, new media art have at one time or another been digitally pushed into the artistic space. In recent years, acceptance by the established big boys of art, like the Tate Gallery, Museum Of Modern Art (MOMA) and the Getty Foundation, has given more credibility to the medium.

“There is a similarity with the rise of photography as an art form,” Ikkan adds.

In this day and age of indiscriminate downloading and copying of virtual data what’s the likelihood of not finding copies of your art popping up on other walls? There’s honour among collectors, it is presumed. Meticulous documentation ensures the veracity of the piece that is acquired. As in any purchase, the gallery’s reputation is paramount. Ikkan adds that collectors are screened to ensure the art doesn’t fall into unscrupulous hands.

The challenge is to get enough works out into the market so that there is more noise made about it, and a secondary market can emerge.

Meanwhile, teamLab continues to push the boundaries. It is hoped that an upcoming exhibition at the Pace Gallery in New York, and possibly one in London will help to give virtual art greater resolution in the real world.

You might also want to read:

A Holo Victory For Mankind’s Future

This article was first published in STORM in 2014.

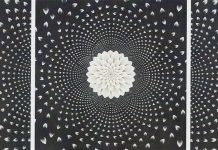

Main Image: teamLab — Loving World