IN CHASING success, many organisations may not be equipped to handle it when they do catch up with it. History is littered with big names that have burnt to a crisp when they finally step out to enjoy their day in the sun.

General Motors, Ford, Time-Warner, Sun Microsystems, Dell, Wang Laboratories, Kodak, Sears, The Washington Post and Sony all know how crushingly difficult it is to sustain success. Success is perilous, contradictory and disabling — with countless paradoxes and counter-intuitive pitfalls. Just ask the Foxconn Technology Group. With a customer list that includes Apple, HP, Nokia, Microsoft and Nintendo there’s no denying its success. But at what cost to workers and the Taiwanese company’s reputation?

In 2010 there were at least 14 suicides, a cluster which shone a bright light on Foxconn’s practices and those of its clients like Microsoft, whose own success in inextricably tied to Foxconn’s ability to manufacture components at incredibly low cost.

Inevitably, questions were posed about what prompted the suicides; was it the long working hours, relentless tedium, deprived relationships, consecutives days on-site, low wages…? Are such poor employment conditions part-and-parcel of becoming a success? Contradictory voices, however, wondered if the success and size of Foxconn’s clients, like Apple, predictably opened it up to extreme enquiry, inspection and commentary, especially in light of the suicide rate being lower than China’s average of some 23 per 100,000.

The troubles at Foxconn re-ignited with workers at the Xbox production line threatening mass suicide in January 2012, over plant closures, transfer arrangements and severance pay, leading to the conclusion that Apple, Microsoft and many others could not offer their consumer electronics at current prices without Foxconn curtailing its labour costs.

It costs around US$170 (S$220) to manufacture the latest iPhone at Foxconn compared to a conservative estimate of US$340 in North America.

On The Other Side Of Success

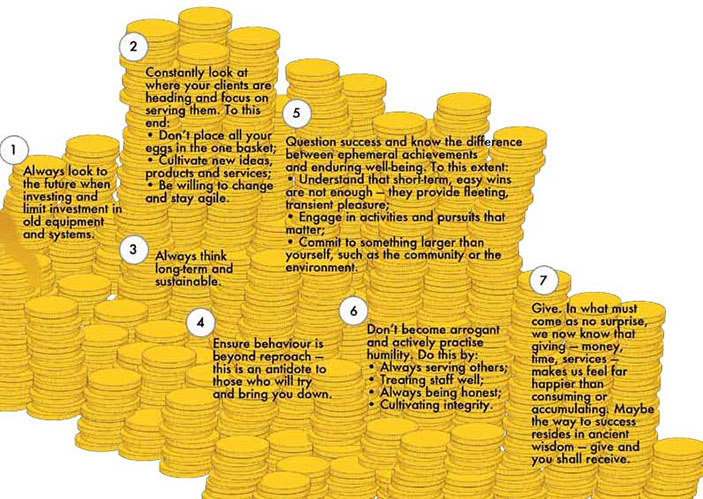

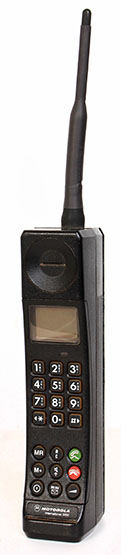

Professor Vijay Govindarajan, co-author of The Other Side of Innovation, writes that successful companies tend to make big investments in old systems and equipment which prevent the pursuit of fresher, more relevant investments; they fixate on what made them successful and fail to notice when something new is displacing it; or focus on the marketplace of today without sufficient attention being given to the future. All three approaches can be disastrous and help explain why so many organizations struggle with success.

After building and selling the world’s first mobile phone, Motorola dominated the industry in 2003 with the Razr, the biggest selling mobile phone ever at that time. Unfortunately for Motorola, it failed to focus on where consumer tastes were heading — email and data capability. Apple, LG, Samsung and the rest, powered by their software development, vanquished Motorola so quickly that its phone division was spun off in 2011.

Likewise, AOL-Time-Warner was riding a wave of success that was worth a cool US$350 billion in market capitalisation when they merged in 2000. A year later the company’s market capitalisation had plunged to US$208 billion and by 2009 the company’s value was just US$65 billion.

Such a rapid decline in fortune is staggering and highlights the inherent difficulties of maintaining success.

More importantly, it underscored the massive egos that drove the merger in the first place and how tough it is to integrate disparate cultures and strategies. Research In Motion, makers of the Blackberry, have also watched their devices fall from a peak of 55% of the American smartphone market.

But it is not just corporations that can fall prey to success. Entire nations have witnessed the same plight. Italy, as recently as 2010 was the world’s seventh-largest economy. Today it is teetering on the verge of collapse, threatening to derail this once booming epicentre of la dolce vita. And what of China’s success, the self-proclaimed “peaceful rise”. Coal is China’s major fuel and while that’s good news for the Brazilian, Australian and the US economies, it’s bad news for the planet. There’s no doubt our global success — our economic and industrial triumph — is pushing our planet to the brink.

Empire Building And Collapse

Around A.D.150 the Roman Empire was so great and so powerful that few could have imagined its collapse.

Paradoxically, the sheer size of the empire was a major reason for its demise. The Romans had great difficulty managing the vastness of their domains — supplying their army, maintaining communications, administering their people — resources were stretched to the limit. The Roman Empire became arrogant, bloated, slow-moving and corrupt. Which encouraged its competitors to topple it.

At the height of America’s power, another paradox of success has become clear — resentment and antipathy.

The USA, often the centre of global attention, is also one of the most hated, especially with President Donald Trump at the helm — a result of foreign policies, lack of aid, use of torture and military force and building walls rather than mending fences. As much as it appears counter-intuitive, enmity and hostility are all too frequent downsides of success.

Apple knows this all too well. At the end of 2011, Apple was being sued by Via over chips in various gadgets like the iPod, iPad and iPhone. Via claimed Apple had willfully infringed patents. The legal action was widely believed to be connected to ongoing disputes between Apple and smartphone maker HTC. Apple has also had numerous legal fights with Samsung in the US, Europe, Australia and South Korea. Surely, if Apple were not so popular and incredibly wealthy then it would less likely be a target for legal action.

There’s no doubt that some organisations take great pleasure in seeing successful competitors brought down.

If companies actively strategise to derail, unseat and sabotage others then perhaps this is another unwanted cost of being successful. Germans have a concept known as schadenfreude, or enjoyment in the misfortune of others, Australians refer to the desire to bring down successful people as the ‘Tall Poppy Syndrome’. In a strangely ironic twist, the new media that prospers hand in hand with Apple offers easy avenues for spreading malicious rumours, so much so that social media is really a double-edged sword for most corporations.

Success may also entice companies to place all their eggs in the one basket — believing future success can be tied to present triumphs. The problem comes, of course when tastes change — success can flounder with mind-blowing speed. One needs look no further than Sony Music which had pinned its future market success on Mariah Carey. When she ceased to be a commercial juggernaut, the paucity of Sony’s stable of talented musicians nearly ruined the entertainment behemoth. Sony hadn’t cultivated a solid repertoire of acts, choosing instead to throw its considerable resources behind Carey, believing this was the way to maximise its success.

Success often begets more success but at what cost. While the causes of the largest bankruptcy in American history, that of Lehmann Brothers are manifold and complex, there is little doubt that malfeasance and avarice played their part. Instead of being satisfied with being the fourth-biggest investment bank in America the company engaged in cosmetic accounting tricks to maximise success. The result was devastating — bank debt of US$613 billion and bond debt of US$155 billion — not to mention the effect the Lehmann collapse had in triggering global volatility in financial markets and the ensuing Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

Reviewing Success

At the end of the 1980s, Western nations paused to ask whether success was all that it was cracked up to be. Questioning success was a sentiment that gathered much momentum. Of course the Black Monday stock market crash and ensuing recession of the early 1990s helped focus our attention. But then, perched there on the cusp of a material and economic re-evaluation, we tipped back, ignored the doubts and plunged headlong into a renewed obsession with success — an aspirational hedonism that left no room for doubts about the price that may have to be paid.

Western Australia experienced an economic boom that made it the envy of the world — satisfying much of Asia’s hunger for iron ore, liquefied natural gas, bauxite, gold and diamonds. And while the state and its capital, Perth, experience unprecedented wealth, the corresponding rise in violence, ugly development, inflation, traffic and dislocated families are surely a concern.

Successful companies too, are crying out for labour and resources and trying to cope with the challenges of rapid growth: What happens to core business? How do you keep a business philosophy on track? How do you create the headspace to cultivate new and creative ideas? How do you manage disparate and diverse workplaces?

Managing Work Life Balance International’s benchmarking survey of more than 300 work-places found that people have accepted the idea that working long hours is good — a type of socially sanctioned disorder. As a result, the survey found that time spent at work has increased 25% but decreased productivity in a cross-section of work places. It seems that the drive to be successful has impaired our ability to see what actually makes us productive. This diminished capacity was recently reported in the Harvard Business Review, which found that only 10% of managers spent time on work that actually delivered long-term benefit to the business.

You might also want to read:

Work Your Way From The Brink Of Death

How Tourism Affects Our Population Numbers

Success Can Be Tragic

Many of us would know people who should feel financially secure but instead are anxious and indifferent to their success. Instead of basking in the warm glow of accumulated achievements they feel they are swimming frantically to keep afloat, to ward off failure. And what happens when success is short-lived and the plunge that follows is unexpected? Following each stock market crash, there is an accompanying raft of suicides and emotional and marital breakdowns.

The German billionaire Adolf Merckle, one of the world’s richest people, David Kellerman, the Freddie Mac CFO and many others committed suicide as a result of the GFC. In fact, success and fame regularly appear bittersweet — an almost assured descent into self-destruction.

Over the past decade the perils of success have been studied at great length. Academics now talk about the hedonic treadmill, a psychological dilemma where people hunger for more and more pleasure only to feel let downand dissatisfied. On such a treadmill people lustfully covet, consume and attain only to experience ever diminishing returns from their spoils, where needs remain unmet. Terms like the hedonic treadmill and ‘miswanting’ (wanting things that fail to deliver satisfaction) are fast becoming part of our lexicon. Thanks to the work of people like Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman, we also know that beyond a certain level of income, more money delivers no additional increase in happiness.

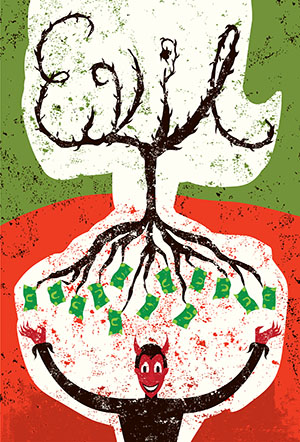

What’s more, psychologist Professor Barry Schwartz has shown that with material success and abundant consumer choice, affluent societies have made no gains in well-being. In fact, Schwartz demonstrates that people who try to maximize every possible choice and domain of their lives — material goods, occupation, life partner — turn out to be less happy, less optimistic and more depressed. Perhaps it’s assimple as the lesson in the Bible, ‘The love of money is the root of all evil.’

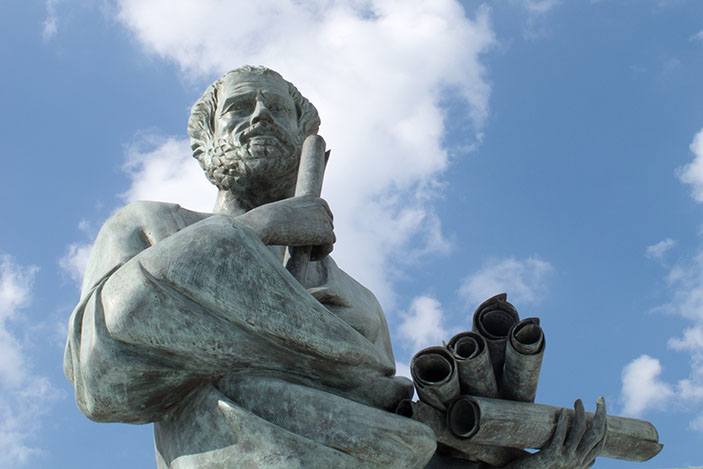

Borrowing heavily from Aristotle, positive psychologists tell us that pleasure is not enough for lasting happiness and well-being. The truly successful life, they argue, requires that one be ‘engaged’ in what one does and utilize one’s signature strengths. This is what Aristotle called the good life and what self-help books today call ‘flow’. However, Dr Martin Seligman, one of the founders of Positive Psychology, goes further and says for a meaningful life, one must also have a commitment to, and act in, service of something larger than the individual.

This article was first published in STORM in 2012.

Main Image: Who is Danny / Shutterstock.com