PHILOSOPHERS have long queried how the role of attachments and detachments form a constant series of overlapping conundrums that plague us from birth to death. Where lies the answer to this riddle?

Let’s journey back to the past to get some direction.

According to Hindu legends, Nammalwar, an ancient Tamil poet and one of the 12 Vaishnava saints, did not cry when he was born. His parents left him in a temple from where he moved to a nearby tamarind tree and sat in meditation inside a hole.

For 16 years he didn’t move or speak.

The legend goes that the brightness of his halo brought another poet, Madhurakavi, to him. To trigger the meditative Nammalwar, Madhurakavi asked him a metaphysical question.

“If a small one is born in the stomach of the dead, what will it eat and how will it exist?”

“it will eat that and exist there only,” said Nammalwar.

Seemingly a plain question and answer, the episode is being interpreted in various ways by scholars to this day.

Some interpretations explained that the “dead” implies the mortality of the human body and the “small” implies the soul. When a soul is trapped inside the body and if the soul assumes itself as the body, what will be in its destiny is the question.

The soul will go through the destiny according to the body’s actions is the answer, which implies that the soul will not attain salvation as long as it assumed itself as the body and not be different from it.

Another explanation goes that the “dead” signifies the way the body grows through a cycle of dead cells and new cells. The “small” signifies the atom, the smallest component of matter. Atom signifies life. And life exists depending on its own actions.

Learn To Let Go

Simply put, Man’s course of life depends on his own actions, and as one grows one should understand the transient nature of human life and move on without attaching oneself to attractions or bonds of life. Besides the metaphysical question and answer, the context of a tamarind tree also is significant here.

Tamarind, when it is tender, is all green and sticks closely with the skin. It will be difficult to peel off the skin from the pulp. But as it grows into a ripe fruit, the pulp become loose and detached from the skin which is only a shell now. The metaphor alludes to the need to discard worldly attachments as one grows and matures; exist, but without attachment.

Now the concept of detachment is being advocated extensively by many Asian philosophers. One of Buddha’s key teachings is about dropping attachments. Buddhist monks all over the world practice this concept in their lifestyle, living with minimum needs.

But wouldn’t life be very boring and monotonous without the attachments and passions — trappings or whatever — and desires and dreams?

Vivekananda, the 20thcentury Indian philosopher answers that one should work with great passion and have desires. ”Surely it is better to be attached and caught, then to be a wall,” he said.

But, at the same time, one should have the awareness and the ability to quit it at will.

Chinese philosopher Confucius emphasised similar thought processes on living with attachments to life and relationships yet detached at the same time.

In all relationships there is a need for distance he said according to the classic work, Lun Yu, a compilation of Confucius’s teachings. Relationships should be like a lotus flower which is bloomed yet not yet fully bloomed. You enjoy the relationships and be delightful in each other’s company, but at the same time, one should be independent in one’s own thoughts and actions.

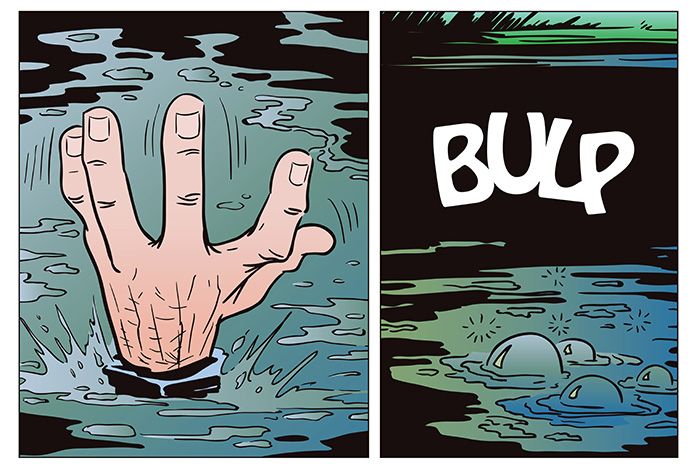

Life And Water

Talking about aging and maturing, in life, the 7thcentury AD Hindu sage Adhi Sankara tells you that human life is so unpredictable and uncertain, rolling like a drop of water on a lotus leaf.

Another ancient Tamil proverb advises you to live life like a drop of water on a lotus leaf — the drop will roll over on the leaf but will never get stuck or absorbed by the leaf. Similarly, human beings should be involved in life, but should not get stuck with the myriad attachments.

And in the Bhagavadgita, the Hindu holy script, Krishna tells Arjuna that no harm would affect an individual who keeps doing his duty without any selfish motive or attachment, just as the lotus leaf is not affected nor immersed in water although it floats all the time in the water.

Gautama Buddha picked up the lotus simile to illustrate enlightenment. He said that enlightened human beings don’t get affected by worldly life although they are born and live in the world, just like the lotus leaf, which floats unsoiled by the water it grows in.

Lebanese American poet Khalil Gibran’s poem On Children— “Your Children Are Not Your Children.” — is an oft-quoted text on the concept of detachment. The poem emphasizes the importance of giving love to one’s offspring but at the same time not to get too involved in them since they have their own lives and destinies. This was a recurring theme in his poems.

“Stand together, yet not too near, for the pillars of temple stand apart, and the oak tree and the cypress grow not in each other’s shadow,” he said in another piece.

Buddha loved taking similes from the environment he lived in. Like Nammalwar, he also draws the tamarind tree to illustrate a point.

The Dhammapada, the work that contains Buddha’s teachings has this story: Once staying in a tamarind grove, Buddha picked up a handful of tamarind leaves and used them to explain to his followers that there are a lot of things that he found about life, but he has told them only very little; as little as the small amount of leaves in his hands compared to the vast number of trees in the grove.

Letting Go

In fact, most Asian sages drew their similes from nature.

Lao Tzu, the 6thcentury BC Chinese sage said in his Tao Te Ching, the essence of all his teachings, that living plants are tender and yielding, while the dead are stiff and would break. Similarly, those human beings who are soft and yielding would enrich themselves in life and those who are rigid would wither and perish. As one advances in age, the wise learn the art of letting go. Lao Tzu tells you that by letting it go, everything gets done:

“The ego is a monkey catapulting through the jungle: Totally fascinated by the realm of the senses, it swings from one desire to the next, one conflict to the next, one self-centered idea to the next. If you threaten it, it actually fears for its life. Let this monkey go.

“Let the senses go. Let desires go. Let conflicts go. Let ideas go. Let the fiction of life and death go. Just remain in the centre, watching. And then forget that you are there.”

Indian philosopher J. Krishnamurthy’s core teaching also emphasizes this theory of observing one’s life, with a “choice-less awareness”.

According to Chinese legends, Lao Tzu was tired of the society/kingdom he lived in and left the region towards the west on a water buffalo. At the western gate a sentry asked him to compile all his teachings for the benefit of the country. The result was the work, Tao Te Ching, with 81 verses that is a guide to proper living.

The stories say that he went to India and met Buddha. Some stories also refer to him as contemporary of Confucius. That, perhaps, could be a reason why we find a lot of similarities in the thought processes and the teachings of these sages.

Although various philosophers in various periods kept discoursing about life, the quest for truth of life continued to intrigue mankind. As each individual with the thirst explored life, he or she evolved and became enlightened in his or her own way.

And Zen…

Zen is one such quest in the post-Buddha period. While Japanese monk Myoan Eisai from 12thcentury AD is attributed to be the pioneer of Zen, Dogen Zenji, from 13thcentury AD is considered to be the greatest Zen master.

Both sages looked for authentic teachings of Buddha and evolved their own concepts. Today, six essential concepts form Zen Buddhism. Among them, the concept of Sartori is the original state of mind of human beings before it was ruffled with worldly desires.

In Sartori condition of mind, the individual lives life with total joy, discovering each day as it comes. He or she experiences each moment newly as it dawns. This is like a child’s joy of discovering things and looking at everything around you as new and enthralling. In this kind of enlightenment, the curiosity never fades and there is no burden on knowledge that obstructs the joy of discovery.

Life doesn’t give you easy answers.

And one of the philosophers might have answers for some of your queries.

Since each individual is different, each has to go through the grinding process of discovering. Wisdom lies in discovering new passions as time moves on. Even as the old passions fade away, allowing new ones to replace them would bestow one with peace and tranquility — like the flowing of the running water which is fresh forever.

Images: Shutterstock