DESPITE having left the Singapore Zoo and the Night Safari several years ago, Bernard Harrison is still remembered for his role in creating it.

When Prof Kirpal Singh of the Singapore Management University (SMU) was tasked by Marshall Cavendish to write a quartet of books, he turned to longtime friend Harrison.

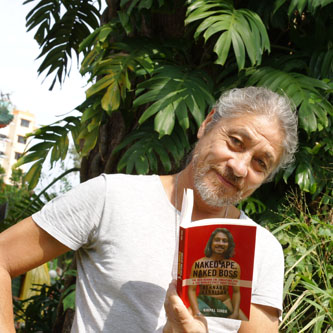

Naked Ape. Naked Boss (2014) took longer than anticipated to complete, and the end result features a provocative cover of Harrison in a Garden of Eden pose with nary a stitch on save for a generous leaf.

Harrison’s reputation was built on his work as CEO of the Singapore Zoo, which till today is considered among the top zoos in the world. A lot of its earlier success was due to Harrison’s unconventional leadership style and willingness to try new ideas. He empowered the right people to get on with things, rather than parachuting talent and micromanaging them.

When the zoo merged with the Jurong Bird Park, the clash of cultures led the free-spirited Harrison to exit in 2002 and set up his own eponymous consultancy.

Some may feel his work at the Singapore Zoo may not have been completed. As Kirpal poignantly asks, who remembers any of the CEOs after Harrison?

The outspoken Harrison now resides in Bali, where he can halve his living costs and still return to Singapore almost monthly, mainly using Singapore as a hub for his consultancy regional work. Dressed a la Bali, in a plain grey tee-shirt, dark board shorts and bright blue Crocs, he carries off the ensemble, complete with fanny pack and trademark shaggy mane tamed into a tail.

He talks to STORM.SG about the book and other issues about the global zoo.

STORM: What does a zoo do for a community?

BERNARD HARRISON: They give an outlet for children, especially. They provide recreation, education and conservation — three very critical areas. Conservation awareness is the most important thing it can offer to children. After you educate them, you empower them to go away and do something — stop your grandmother from using rhino horn, or to get people to stop eating sharks fin.

There are 10,000 zoos in the world. 1,500 belong to serious zoos associations. I think 90% of zoos should shut down.

They are horrible stink holes. India is the only place in the world that’s doing something about it. The Central Zoo Authority controls the 400 zoos in the country, and they’ve closed down 140, with another 100 pending.

The biggest problem is what you do with the animals. So, the zoos remain because these animals can’t be released. It’s an animal welfare issue.

But the zoo here has been a bugbear of mine. It should do a hell of a lot, but in Singapore it’s so expensive*. The people who should go to the zoo can’t afford to.

STORM: What are the options?

HARRISON: You could go to a national park. I go to Africa every year. I’m going gorilla tracking in Uganda soon. It costs US$500 for one hour to see them in the wild. These are mountain gorillas, and it takes about three hours of trekking along 70° slopes.

But if you’ve been to Taman Negara, in Malaysia, you can see absolutely nothing. I’ve been to Taman Negara for three days. I saw one butterfly.

Here’s an interesting statistic. Tanzania has Serengeti, and it’s 4.5% of area of Tanzania, which is 945,000sqkm. Singapore, which has an area of 710sqkm, has four national parks — Central Catchment Area, Labrador Park, Bukit Timah and Sungei Buloh — which together form 4.5% of Singapore’s land mass. We have the most accessible national parks.

STORM: How did the idea of the Night Safari come about?

HARRISON: I got a call from the PUB asking what I was going to do with the extra 60 ha of land that we had after the Singapore Zoo had been built. I said we are going to do lots of stuff. We had no idea, actually. Then the PUB asked us to send in a plan for what we intended to do with the space.

So I called my Chairman, Dr Ong Swee Law, and we had lunch meetings with captains of industry, and they came up with some inane ideas — golf course, plant durian trees. Then Lyn de Alwis, the Consultant, Director and Design Advisor of the zoo, said why not create a night zoo.

Dr Ong was not a typical civil servant. He asked Lyn, if it had ever been done before. Lyn said it hadn’t. Dr Ong said if it’s never been done, let’s do it. That’s the sign of an entrepreneur.

I had another project in Singapore, which had never been done, and I approached all these entrepreneurial Singaporeans to invest in it. They asked if it has ever been done. I said No. They said ‘oh…’ and backed off.

Changi Airport is designed on Schiphol in Holland. The MRT is designed on the MTR Hong Kong. We are so scared to do it first. That’s the problem. We are so constipated in Singapore.

STORM: Who would benefit from reading your book?

STORM: Who would benefit from reading your book?

HARRISON: Kirpal said it’s about management — how you manage staff, people. But that’s because he’s from SMU and he was charged to write a book about management by Marshall Cavendish.

To me it’s just a biography. It was actually meant to be a far more serious book. It was commissioned almost like an academic book. There are lots of little anecdotes from friends, which were meant to be annexes. Then the publishers decided to make it a lighter read.

STORM: What has your experience managing the Singapore Zoo taught you about management?

HARRISON: Quite a lot. I have an interesting management style which one consultant told me was management by exception (where only significant deviations from the norm are addressed). I hire someone based on a lot of personality tests, pay them what is fair and then let them get on with it. I see them once a week.

You place total trust in your staff and you interact with them. It’s the total opposite of micro management.

Management by exception worked very well for me, but it’s hard to do it in an existing organisation.

In any case, people who work in a zoo are nuts. They like animals. They are empathetic with the cause. They are idealists. They are not fighting for the CEO position. So your in-house politics is low anyway.

STORM: What significant projects have you working on since going solo?

HARRISON: The problem with doing consultancy work is that only one in 10 things materialise. We’ve done a zoo in Rabat, the capital of Morocco, and one in Twycross, UK. We worked on the night safari in Chiang Mai, and are doing one in Xiamen.

We do a lot of master plans. In China, they need to develop master plans to submit to the government to get the land. Once they secure it, then a percentage of what they sell as residential or commercial parcels will go towards recreational spaces.

STORM: What are your thoughts on the killing of Marius the giraffe by the Copenhagen Zoo?

HARRISON: We eat 300 billion kilogrammes of meat every year. They are mainly in the form of chicken, cows, goat, fish. And we kill them in the most bizarre and ghastly ways. It’s pretty bizarre that one should get so worked up about a giraffe that was killed. The Copenhagen Zoo told the press they are going to put down the giraffe, and invited students to watch the dissection. It was done in a very Danish systematic, logical and methodical way.

If it was me, I wouldn’t have told the press. I would just have done it. All zoos do this.

If you have too many deer, you either put them down and feed them to the animals, or put them down and we have a barbecue. Unfortunately, that’s the way it is. The incident in Copenhagen was taken out of proportion.

We had a tiger escape from the Night Safari in 1996. It was a hand-reared fully-grown tiger. It was very friendly but totally an unknown entity. There was a tram of Japanese tourists and this tiger walks past. “Wow, so real…this is so fantastic…ah…so!” the impressed tourists must have said.

In the end, they cornered it and were trying to tranquilise it, but it charged at the shooters. With the dart gun, there’s someone with a rifle and so it was shot dead. We had to tell the press about it because everybody had seen it.

In that kind of public relations situation, you shouldn’t talk about it by name. You shouldn’t say Timmy the tiger was killed. You shouldn’t say it was hand reared. You shouldn’t personalise it.

STORM: How much is a tiger?

HARRISON: A live tiger costs US$50,000 in China, where it’s prized for its bone, flesh, penis and claws. That’s why they are going extinct. India’s tigers are still being poached. They have tiger farms in Thailand, which send around 100 tigers to China. And there are some tiger farms in China.

It raises an interesting moral issue. I have no qualms about killing crocodiles. It’s an apex predator, a cruel animal. But killing tigers is immoral, although it shouldn’t be.

They sell chimpanzees and gorillas as bush meat in Africa. Their flesh is four times costlier than the most expensive meat available. It’s a highly prized commodity. They smoke it and ship it, quite often to African embassies in London.

Chimpanzees have 98.7% similar genetic material to humans, and so if I have a problem with tiger farming, then how about chimpanzee farming?

It’s a moral dilemma. Where do you draw the line?

This article was originally published in STORM in 2014.