“THE horse is here to stay but the automobile is only a novelty, a fad.”

So said, the president of the Michigan Savings Bank to a certain Horace H. Rackham, a lawyer and one of the original investors in the Ford Motor Company, founded by the legendary Henry Ford, in 1903.

As luck, or better judgment, would have it, Rackham ignored the advice and, at considerable personal cost, acquired a sizeable share of the newly formed company for $5,000. He eventually sold his share to Henry Ford’s son in 1919 for a cool $12.5 million!

Not bad for a 16-year investment, eh?

Of course, one could argue that the poor old president of the Michigan Savings Bank, should be forgiven for thinking that automobiles were nothing more than a fad, given he probably was not a technologist, or a horse specialist, for that matter (at least I did not find any evidence of such expertise).

But predictions of this sort, are not limited to non-specialists. The fascinating history of technology is full of examples of the true experts of a field who get it badly wrong on the assumption that the next predicted wave of change is nothing but a misguided bout of enthusiasm.

One such example is the assertion by Ken Olsen, the founder of Digital Equipment Corp., who, in 1977, predicted that “there is no reason anyone would want a computer in their home”. To be fair, he was commenting on the prospect of using computers for the purpose of home automation (image recognition to open doors, sensors to control temperature, etc.), rather than owning a personal computer, but, still, as a trained engineer and a founder of a major tech company, the fact that he viewed such suggested use cases for computers as hype is rather curious.

Quite frankly, predicting the future is not easy. Or as a wise person once remarked, it is easy but getting it right is not! So, maybe we should not be too critical of those who were bold or courageous enough to go on record with their predictions.

And yet, I always think twice before sharing my thoughts with those who corner me to inquire about my thoughts on the future of specific topics such as artificial intelligence (AI) or blockchain.

While trying to second-guess the future is quite tricky for specific or narrow topics, making broad predictions about a major subject such as Big Data is a different matter altogether.

Is Big Data A Fad?

Before giving a definite yes or no answer to this question (and unlike a seasoned politician, I shall give you a definite yes or no in the end), let’s drop the “Big” in the “Big Data” and look at the plain, simple “Data” on its own.

In my recent book, Data Unplugged, I define Data as “a collection of facts, usually the results of observations, experiences, or experiments, or a set of premises used for reasoning, and from which conclusions may be drawn or decisions may be made, within a given context. Data may consist of numbers, a set of characters, images, sounds or other sensory input.”

In my recent book, Data Unplugged, I define Data as “a collection of facts, usually the results of observations, experiences, or experiments, or a set of premises used for reasoning, and from which conclusions may be drawn or decisions may be made, within a given context. Data may consist of numbers, a set of characters, images, sounds or other sensory input.”

Data Details

This is a rather detailed definition and includes the most important points one needs to note about data:

What it is — a collection of facts or a set of premises;

How it is acquired — through observation, experience or experimentation;

What it looks like — a combination of numbers, characters, images, sounds or other sensory input;

And perhaps most importantly, What it is used for — reasoning, drawing conclusions or making decisions, within a given context.

While each one of these points is worthy of its own dedicated discussion, for our purpose here, let’s consider the decision making aspect of the above definition.

Data Usage

To start with, I am going to claim that all of us, regardless of our individual background and area of expertise, already use data in making decisions. Of course, we may use different sources of data, or different aspects of the same data. Some of us may be more sophisticated in how we interact with data or what technologies and tools we utilise and some of us may rely mostly on the so-called rules of thumb and experience alone but remember that the definition of data given above catered for such cases too.

In other words, the only alternative to not using data in your decision making is if you made decisions randomly, for example, by throwing a dice at each decision point.

Secondly, most of us intuitively appreciate that more relevant data is probably good, at least most of the times (and potentially bad if too much of it results in analysis paralysis).

Now, to stress this last point, let’s take the context of buying a house as an example. This is an activity that is likely to be familiar to most of us in that we have either bought a house ourselves or have seen enough people do it to get a basic feel for it and what it involves. But how one decides which house, out of potentially many, to buy?

In the past, when life was much simpler, buying a house may have been a reasonably straightforward thing to do: You had a certain criteria for your dream house, such as number of rooms, number of floors, neighbourhood, price, etc., and you looked for something similar and when you found one that matched your requirements you acquired the deed of the property in exchange for money.

While the above scenario sounds simple, its data requirements are actually quite involved. You still needed to see various houses and compare their current status, size of the rooms, etc., to make your final decision. In other words, without the latest information about the various characteristics of each house that you reviewed you could not make a reasonable final choice.

As societies evolved, human interactions became more complex and standards and regulations were introduced to safeguard the rights of consumers, more information was generated which could potentially affect one’s decision about buying a house. This is why buying a house today is anything but simple!

Data Deluge

For example, imagine you are planning to buy a house ahead of your impending retirement. You choose a neighbourhood that is quiet and seems to be already popular with many retirees who, just like you, value a peaceful and noise-free environment. You are lucky enough to find your perfect house in this seemingly perfect community. Just as you are about to go ahead and commit yourself to put an offer, your annoying friend, Parviz the nerd, who has a unhealthy obsession with data, alerts you of the local council’s recently published 10-year plan that includes a major expansion of the area with a massive mall and a major entertainment complex.

From the outset, this looks like a good reason to believe that the value of your dream house is likely to increase rather quickly, given the proposed expansion plan so, maybe this is a good investment after all. But if all you care about is living in a quiet area and enjoying your retirement then, maybe you should give this one a miss and keep looking elsewhere.

The bottom line is that having this extra piece of information helps you make a more informed decision and reduces the possibility of regret after the fact.

One could easily expand the above scenario and include more sources of data that could have a potential impact on such decisions. Data about the latest crime rate in the neighbourhood, latest proposals on taxation regarding energy consumption of households, or property tax rules are just some of the examples one could think of. No wonder some consider the experience of buying a house as a good way to loose some extra weight!

More relevant data is instrumental in other areas of life too.

One reason the scientists have been able to produce highly effective COVID vaccines in record times in the face of a rampant pandemic is their ability to use more data to test many possible scenarios quickly, resulting in major improvements in vaccines’ quality and significant reduction in the risks associated with them.

Now that we know data is good and more of it, in the right context, can be even better for decision making, what can be said about “Big Data”?

Data Points

The “Big” in Big Data is really there to highlight the impact of the recent technological advancements (by recent I mean the past 25 years or so), such as the rise of Social Media. In particular, as technology enables us to digitize more data, making it readily accessible and transferable from one place to another, we find progressively diverse sources of data (Data Variety) that produce more input (Data Volume) at higher speed (Data Velocity) than ever before.

Also, as we enable more data sources, the possibility that some of the data is incomplete, or incompatible with other sources, increases, which results in more uncertainly in data (Data Veracity).

All this means is that, in response to the explosion in available, and potentially relevant data, for our various use cases, we need to adapt and use better tools and methodologies to deal with the data at hand, but the central message has not changed: Data is useful for all manner of decision making, and more of it, when contextually relevant, is better and can lead to more informed decisions.

Taken in that light, it is difficult and misleading to label Big Data as a fad. Rather, it represents a wave (a technological wave, if you will), that touches every society and, by definition, every member of society.

In fact, data is so relevant to everyone’s proper functioning in the modern world that one can argue that it should be taught as a core subject in schools.

But Big Data, is still in its infancy. And like any other new concept, a mixture of over-the-top optimism and naive understanding of its core tenets can lead to assertions that may/do appear fantastical.

Data Duplicity

This is particularly the case in the start-up ecosystem when countless enthusiastic founders, with the help of their friendly marketing gurus, promise the next best thing since sliced bread, only to fail on its delivery.

That said, these founders’ primary concern is to raise funds quickly, and lots of it too. So, in that context, being bold and over-the-top can pay handsome dividends!

As a general rule though, predictions that deal with complex use cases, which require a harmonic interplay of many external factors, are likely to fail and mostly, but not all, tend to be too optimistic. This is because, by definition, external factors are out of our control and it can take a small change here or there to make the entire prediction fall flat.

In summary, while a number of specific predictions about certain aspects of Big Data can be viewed as faddish, Big Data, as a whole, is a reality that is upon us and is going to get more prominent in all our lives in the future. The sooner we all come to terms with this, educate ourselves and find the best ways to utilize relevant data in our own decision making, the higher our chances of success in whatever endeavour we are engaged in.

Parviz Foroughian is a data strategist, technologist and thinker. He is the author of a newly released book Data Unplugged: Understanding Data and Why It Matters (Write Editions. 2021), aimed at enabling enterprises to be smarter through the discipline of strategizing data.

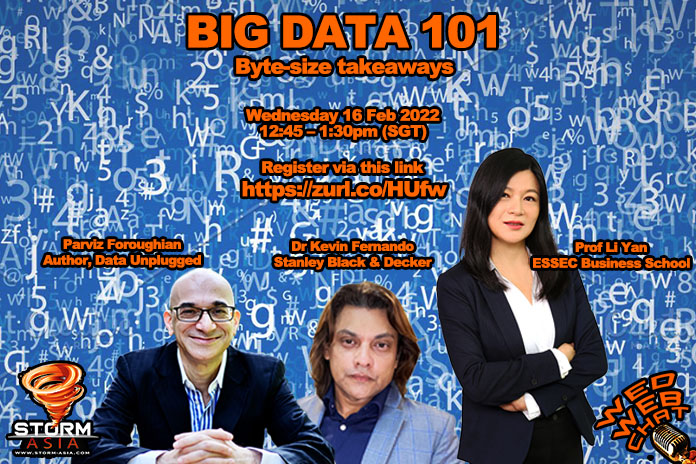

Parviz will be joined by Prof Li Yan and Dr Kevin Fernando on the panel of the WED WEB CHAT — Bid Data 101: Bite-size Takeaways on Wednesday 16 February 2022, from 12:45-1:30pm (SGT). To register for the session, click on this link: https://zurl.co/HUfw