MANY have tried to tame the markets. Most fail, usually after making a series of errors.

While it may seem that professional traders and those in the know are the only ones with an edge, psychology governs the decisions of all market participants. Understanding how our emotions influence our opinions and decision-making processes can make us better investors. But this wisdom can also positively influence our decision-making in general.

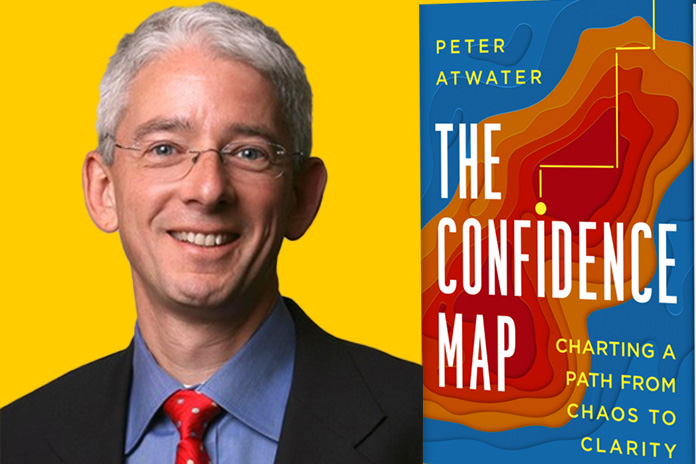

Peter Atwater, an Adjunct Professor of Economics at William and Mary and author of The Confidence Map: Charting A Path From Chaos To Clarity, doesn’t see investors as rational or irrational. But he considers that all investment decisions must be rationalised.

We have to imagine the future in some sense when we buy or sell an asset.

Peter considers psychology fundamental to understanding both markets and how people make daily decisions.

When the crowd is invested in something, it often has more to do with how they feel. Explanations for why they are invested in such assets tend to emerge after the decision has already been made.

He paints a picture of these decisions in what he calls a Confidence Map.

The sections of the map can be applied to many real-world scenarios.

We regularly experience environments where we hope we have intense certainty, but absolutely no control.

If you’re a passenger in a plane, or being driven over a bridge, even riding an elevator, you have no control over anything untoward that might take place.

No Control, No Certainty

When we lack control and begin to question our certainty, things can go from being calm to chaotic in an instant. Picture yourself relaxing in your airplane seat, and suddenly experiencing turbulence. Your mood quickly changes, the atmosphere can become stifling. In such environments we need to be cognizant of the absence of control, in advance of feelings of panic.

Control Without Certainty

A rock climber halfway up the side of a mountain has control over his abilities, but not of what could happen next with nature.

A student taking an exam would have studied hard, but has no idea what questions are on the paper.

In these situations, people have control, but the outcome is yet to be determined.

People do not often appreciate that this dynamic defines our every financial decision; whether borrowing money, lending, or investing.

We are always making up our expectations as the future is inherently unknown. What we miss is that our imagination of the future is entirely a function of how we feel.

In these situations, Atwater suggests that we pause for a moment and realise that our imagination is a mirror. If we are too certain that things will be great or horrible, we could be proven wrong. Every time you are certain something is going to happen; you could be setting yourself up for massive failure. We need to be more open to the opposite outcome and consider how to prepare for either situation.

The actionable advice he gives, is to practice proper risk management. People often associate this with position sizing, stop losses and diversification across asset classes. Atwater suggests emotional hedging. While it may seem like common sense to buy assets people love, you need to hedge those bets with assets people hate, things people absolutely revile.

Managing Probabilities

As for situations where we have maximal control but low certainty, in the Confidence Map this is referred to as the Launch Pad. Atwater suggests you assign probabilities to both success and failure, and to take pause anytime those percentages get very high in either direction.

We routinely accept the ideas of both under- and overconfidence; we can always come up with reasons why the end of the world is approaching. What should you do when the crowd (which you may be a part of) is in a state of panic?

ALSO READ: A.I. Is An Enabler Not A Solution

Panic-stricken

When you panic, it’s usually after the fact. The worst is behind us, but we don’t appreciate it. Any time you see panic, remember that is an over-extrapolation of the uncertainty and powerlessness being felt. This does not mean you’re going to crash tomorrow, but that low is rapidly approaching.

“Panic attacks are exhausting and they ultimately end very quickly.”

He notes that as an investor, you would have profited regardless of which month you bought in 2020. We should appreciate that the crowd only panics when sentiment is extremely low.

Mania is the other side of panic. Both mania and panic can be useful measures.

For example, when you observe panic, the correct mindset would be: The crowd is panicking, I want to be prepared for a reversal when it comes because it’s coming soon, but I also need to focus on staying calm and not over anticipate coming moves.

Psychological Positioning

Another metric Atwater suggests using to gauge the psychological positioning of the market is companies or people who are hated and loved in cycles.

Elon Musk was deeply hated towards the end of 2022; many mocked his acquisition of Twitter and complained about his changes, while highlighting the failures of Tesla.

But at the top of the market, Elon was revered as a godlike figure. His companies are intertwined with many cutting-edge technologies — electric vehicles, artificial intelligence, space travel, wireless telecommunications, crypto and social media. When he is loved again by the consensus, consider that a good indicator that peak market sentiment has either been reached, or is fast approaching.

Defining Confidence

Atwater believes the term confidence is overused, and its interpretation is often ambiguous.

With respect to decision making, he considers the two key definitions of confidence to be:

- Our feelings of certainty, the degree to which things ahead are predictable.

- Our feelings of control. Do I feel prepared, have I rehearsed, or practiced? Do I have the skills to navigate this future that I imagined?

The confidence map is the connection between our feelings of certainty and control and the decisions we make. From how we think, to our preferences, to the stories we tell, the balance affects all our decisions. Control and certainty do not guarantee one another, we spend much of our lives having only one or the other.

Vulnerability is the opposite of confidence; when we are vulnerable, we feel uncertain and powerless. This feeling strongly influences the kinds of choices we’ll make in a crisis. Vulnerability creates an intense amount of impulsiveness in emotion. It creates the feeling of ‘a problem that needs to be solved immediately’, pressuring us into acting without considering the emotional context.

ALSO READ: Fleeing Jerusalem — A First-person Account

Advice For Passive Investors

“Don’t flip-flop, dollar cost average or buy when people are panicking and forget about it. Come back in 10, 20 years and see what you’ve got.” This will prevent you from undoing your well laid plans due to inevitable changes in your emotions, for whatever reason they may occur.

Putting Advice Into Practice

Apply this mental framework to today. Financiers and macro economists have been anticipating a recession for well over a year and many have been positioned on the wrong side of the market for much of that time. The AI bubble has been ripping in their faces, with the highest market cap tech stocks such as NVDA reaching new highs.

Atwater warns of the damning psychological effects of anticipating a recession. “Historically, we have been poor at both predicting and experiencing them.”

He explains that our group behaviour directly sets up the economic environment.

When everyone is anticipating a recession, people will take less risks and be more protected from catastrophes, we could be amid a recession and be totally unaware of it. Conversely when no one anticipates a recession, people feel invincible, taking on bigger risks across a wider range of assets.

In some ways, such as gasoline prices, the anticipated recession was real. The prices at the pump heavily dictate how we feel.

It’s not always foolish to chase the crowd, but it is unwise to chase the crowd late, with no plan, and without having considered your own emotions and hedging against them.