DOES Michelle Yeoh’s recent international success with Everything Everywhere All At Once (EEAAO) serve as motivation to propel the Asian film industry to new heights?

DOES Michelle Yeoh’s recent international success with Everything Everywhere All At Once (EEAAO) serve as motivation to propel the Asian film industry to new heights?

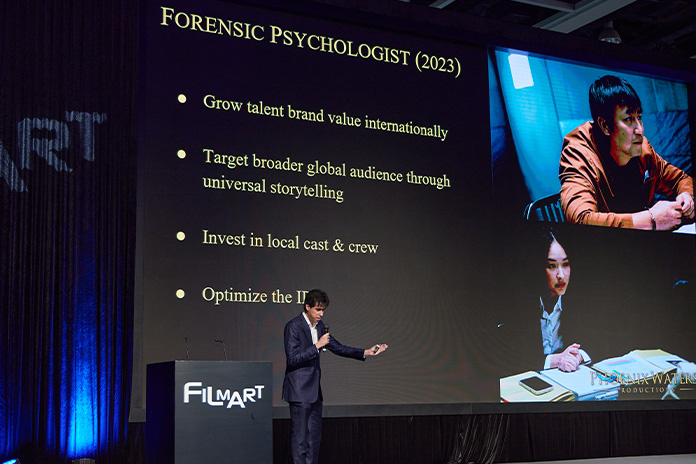

Bizhan Tong (above), Founder of Phoenix Waters, has been actively championing for the resurgence of the art form in Hong Kong, and sees this as an ideal opportunity to push for developing the industry.

How will EEAAO’s success help the Hong Kong film industry?

BIZHAN TONG: The talk I gave at FilmArt recently covers this point. Michelle Yeoh’s success has broken a glass ceiling and serves as a call to invest in the next generation of Hong Kong talent, building their brand value internationally so that Hong Kong may once more be seen as an industry that exports some of the greatest stars in the world. It took decades for Hollywood to recognise in Michelle Yeoh what Hong Kong knew long ago, and hopefully next time they will be swifter.

What is the impact of Asia’s success on the industry, given that awards like the Oscars are adjusting the parameters of their operation to become more inclusive?

BIZHAN: For networks, streamers and studios, decisions are made based on data and the critical and commercial success of Asian fare like EEAAO. This translates into a need to greenlight more projects with Asian leads and/or themes because of audience demand for it. We are seeing over the past few years a desire for greater authenticity so I also expect more local talent will be hired as a result, granting more opportunities for actors in Hong Kong, Singapore, and the Southeast Asia region to be cast in international projects. I would also hope and expect more international investors to spot an opportunity to engage with the Asian film industry as I am doing due to the commercial potential which exists.

I founded Phoenix Waters for this very purpose: To build bridges between the East and West.

One of the differences between the films of John Woo and Tsui Hark in the ’80s onwards, and those released in Hong Kong today, is that Woo, Wong Kar-wai, and fellow filmmakers of that generation told stories with universal themes; i.e. one can grow up in London or Minnesota and still identify with the characters and stories of The Killer, In the Mood for Love, Police Story, Hard Boiled, etc.

Contrast that with today’s films and most feel exceptionally local so are harder to permeate or identify with from a mainstream perspective. Diversity is important and I believe however that the bigger issue that needs to be addressed in Hong Kong right now is returning to universal storytelling while ensuring we do not wash over what makes these stories work for local viewers too.

Why does the Asian industry ride on the coattails of Western affirmation?

It shouldn’t and I respect that many actors in the last few years have gravitated towards mainland China instead for affirmation, where its box office potential can be extraordinary. In 2020, The Eight Hundred became the highest grossing box office film globally for instance. However, generally speaking, the US industry is the most commercially successful in the world, so being able to successfully cross over there enhances a talent’s brand value in a significant way which in turn brings more attention to their local films.

That is one of the many reasons why I am keen to work with local talent, so that international viewers can see that Hong Kong film didn’t end with Jackie Chan, and that the next-generation actors are worth keeping an eye on.

What’s needed for Asian film to be valued on its own merits?

There are still great movies being made across Asia. The late Benny Chan’s Raging Fire for instance or Line Walker 2 are both solid action films, and I am looking forward to Herman Yau’s Customs Frontline. The same is true across Singapore, Malaysia, Japan, and beyond. But Asian film needs more universal storytelling, higher production values, and more opportunities for international collaboration. It needs a healthier ecosystem that isn’t so reliant on independent film, and to embrace more internationally appealing fare.